India’s Book Ban in Kashmir Is a War on Memory

Twenty-five titles — including a work by Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy — have been banned in Kashmir. The crackdown has left authors, students, and booksellers navigating fear and defiance, as the state seeks to erase history and police memory.

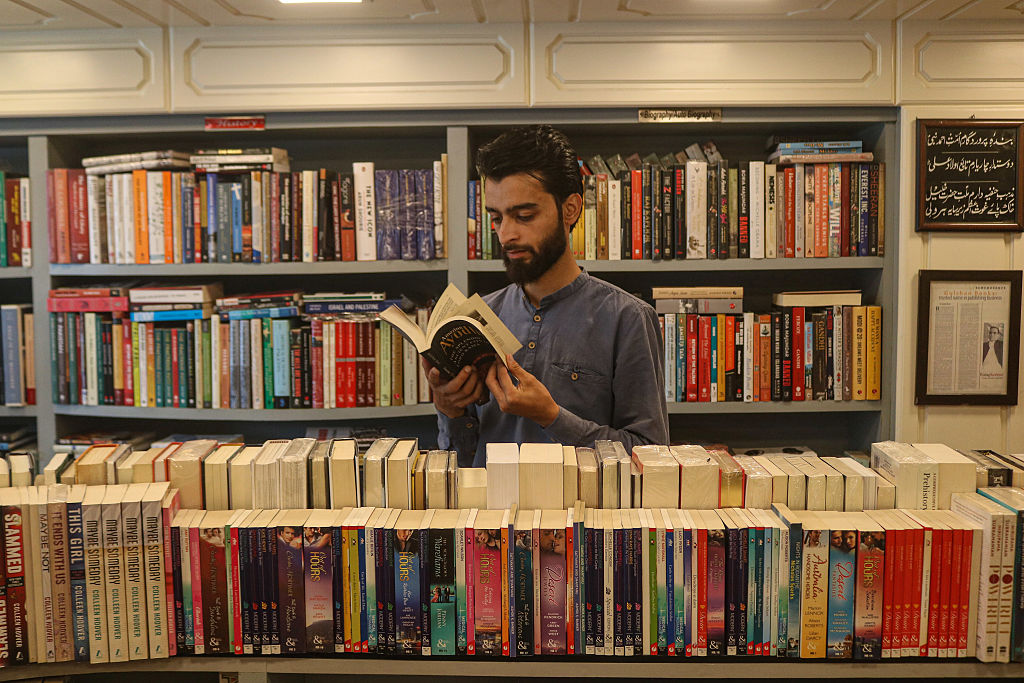

India’s book ban in Kashmir fits into a long history of censorship, from colonial prohibitions on Gandhi to Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. With each ban, not just books but whole perspectives risk vanishing from public life. (Firdous Nazir / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

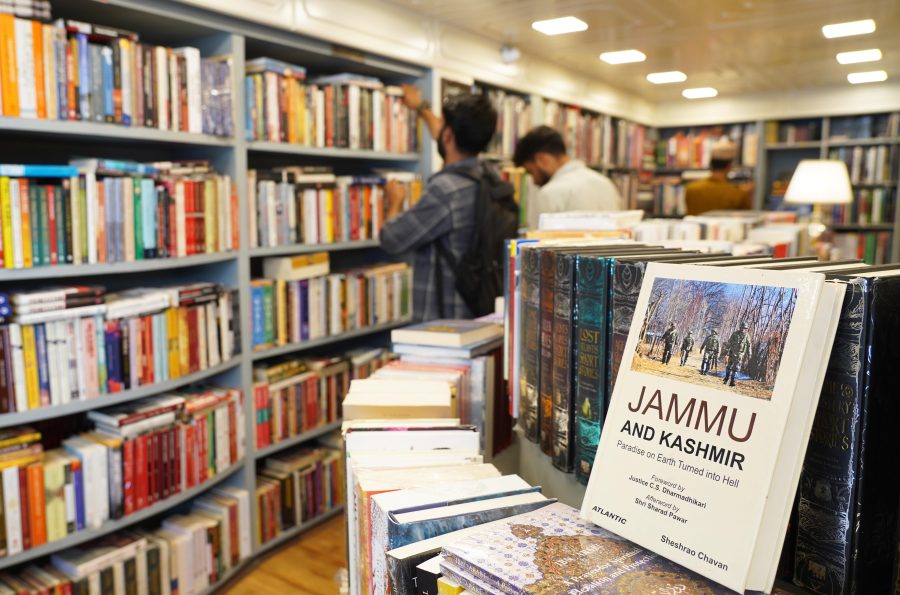

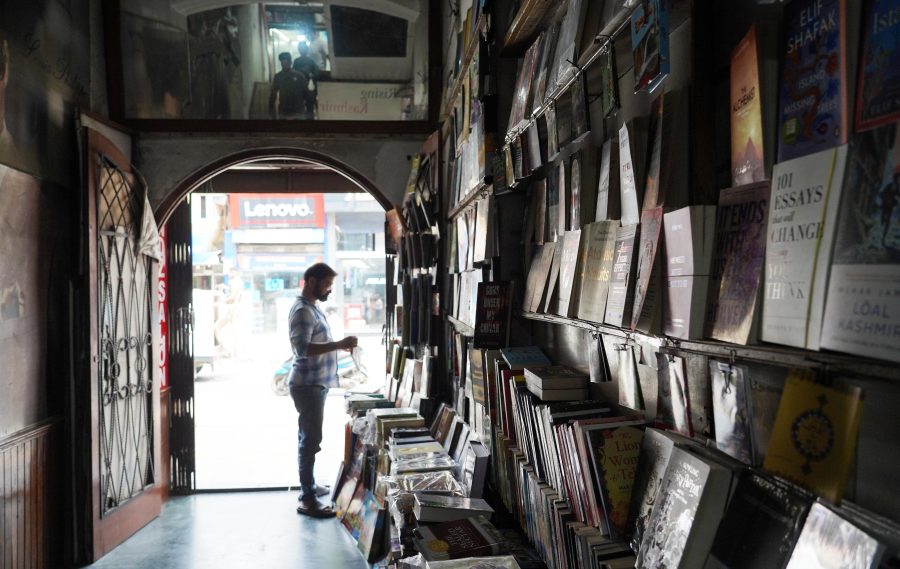

The bookshops in Lal Chowk, in Srinagar — the summer capital of India-administered Kashmir — had been, as usual, places of quiet and repose. But on August 7, police officers started raiding stores, pulling titles from shelves and questioning sellers. By then, the news had already spread online: the Jammu and Kashmir administration had banned twenty-five books. In the hours and days that followed, booksellers scrambled to check their inventories.

These books included works by Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy, along with writers like Sumantra Bose and historian Hafsa Kanjwal. For many, the ban was more than an administrative order; it was another sign of how the Indian government tightens its hold on ideas and words — especially in Kashmir, where the Narendra Modi–led BJP government controls Kashmir directly through Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha.

The stated purpose of the raids, according to police, was “to identify, seize, and forfeit any literature that propagates or systematically disseminates false narratives, promotes secessionist ideologies,” or “otherwise poses a threat to the Sovereignty and Unity of India.”

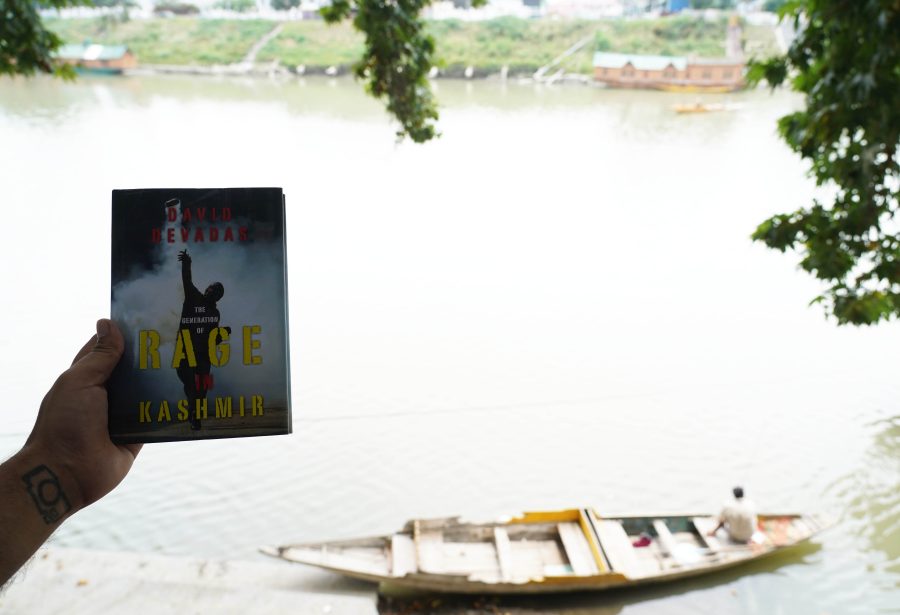

Ironically, the ban only increased interest in the books. As news traveled, demand surged. Readers wanted to know what the state didn’t want them to see. Links and PDFs soon circulated. National and international media picked up the story. If the government intended the ban to pass quietly, it didn’t. Outlets around the world alerted readers to the “book ban in Kashmir.”

Raids on Words

The recent ban on twenty-five books is not without precedent. In fact, it follows a long history of book censorship in India. The roots of this practice trace back to the British colonial era, where works like Mahatma Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj were banned for “advocating self-rule” and “criticizing British imperialism.”

After independence, the trend continued. Books have been removed for reasons ranging from religious sensitivity to political dissent.

In 1988, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was banned following protests by Muslim groups, making India the first country to do so. Similarly, Arundhati Roy’s Azadi faced censorship for its portrayal of the Kashmir conflict and its critique of Indian nationalism.

The recent bans in Kashmir echo these historical patterns. Authorities argue that the blacklisted titles spread false narratives that could influence young Kashmiris toward violence and terrorism, alleging the material fosters grievance and glorifies insurgency.

For the authors involved, it came as a shock.

“When I first saw the news about the ban, I wasn’t aware that my book was included in the list,” said Anuradha Bhasin, one of the banned authors and managing editor of the Kashmir Times, one of the region’s oldest newspapers.

“My first reaction was one of disbelief at the sweeping ban of such a high range and variety of books that have contributed a great deal of scholarship on Kashmir.”

The government’s directive arrived quietly, but its effects were swift and visible.

Police officers entered bookstores in Lal Chowk, Residency Road, and elsewhere — uniformed and armed — and instructed shopkeepers to hand over copies, while searching the shelves themselves. At some shops, books were taken away; at others, they simply vanished into backrooms, out of reach.

Libraries, too, reported sudden audits. Staff were ordered to remove the twenty-five targeted titles from public access.

For the city’s bookshops — many of which have operated for decades — the raids brought legal and financial uncertainty. “We were told these books ‘promote terrorism,’” one shopkeeper said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “But how can a history book do that? It documents what happened, not what should happen.”

Across Srinagar and beyond, similar scenes unfolded quietly. The message was clear: to remember is to risk punishment.

“While the books were taken away, their online copies are still available,” said another bookkeeper in Lal Chowk, “people can still buy them from elsewhere.”

The Shift in Repression

Since the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, which stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its semiautonomous status and brought the region under control of New Delhi — India’s approach in Kashmir has shifted. The crackdown has moved inward, targeting classrooms, libraries, and personal spaces.

Textbooks have been rewritten to erase references to UN resolutions and historical uprisings. Media outlets operate under constant surveillance. Now, the government has turned to literature itself. The 2025 book ban is the clearest example yet: not only silencing dissenting voices but also preventing future generations from accessing the history and ideas that those voices preserve.

In a move unusual but not unprecedented for Kashmir, Omar Abdullah, the Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, took to X to defend himself against online criticism of the ban.

“Get your facts right before you call me a coward, you ignoramus. The ban has been imposed by the LG using the only department he officially controls — the Home Department. I’ve never banned books and I never would,” he wrote.

Abdullah’s post was a response to mounting backlash over police raids on bookstores and the prohibition of titles accused of containing “anti-national” content.

Dr. Hafsa Kanjwal, another author whose work has been banned, recalled her reaction to seeing the list. “When I first saw it, I was confused,” she said.

“The selection felt entirely arbitrary. Some of the books actually align with India’s official narrative on Kashmir, discussing its history, past, and politics in ways that support the state’s claims.”

She added, “At the same time, there are books, like mine — that are sharply critical, questioning India’s legitimacy and portraying its rule in Kashmir as a form of colonial domination.”

“But then it hit me,” she continued. “The government doesn’t actually want any discussion on Kashmir. They are trying to criminalize even the very idea that Kashmir’s status was ever disputed, suppressing any debate about the reality of the issue.”

One Part Orwell, One Part Kafka

The ban has triggered a mixture of anger and disbelief among scholars and students. Many authors said that the accusations of “glorifying terrorism” were absurd distortions of their work.

Some recalled receiving indirect threats or warnings as early as 2018 or 2019, well before the current order. Others said they hadn’t realized they were under surveillance until now, when it suddenly became clear that even academic debate in Kashmir had been rendered legally perilous.

“It is completely bizarre,” author Anuradha Bhasin told us. “I don’t think many of these books glorify terrorism or secession. I can vouch for my own book — it absolutely does not.” Her work focuses on the period after the abrogation of Article 370.

“Ever since the government has tried to portray Jammu and Kashmir as peaceful and ‘normal’ — claiming that terrorism has ended — it has contradicted itself by asserting that certain books glorify terrorism,” she noted, pointing to the inconsistencies in the government’s claims.

One literature student from Srinagar, who asked not to be named, told us that a friend deleted a PDF of Dr Hafsa Kanjwal’s Colonizing Kashmir after hearing about the book ban. “You cannot read in public. You cannot even read in private if someone finds out. It’s like knowledge has become contraband,” he said quietly.

Another student, studying in Delhi, recalled with a chuckle how she and a friend wandered through a market there, amused to find the supposedly banned books openly on display. “We laughed and told ourselves, those who want to read will always find a way — perhaps now, with greater urgency, driven by anxious curiosity.”

In Srinagar, meanwhile, bookshops operate in the shadows. Many have moved banned titles to private homes, while most have handed over such literature to the police, unwilling to court controversy. “We cannot display these books,” one bookseller explained. “But if someone truly wants to read them, they can still be purchased online. We don’t carry any of these titles anymore — no one wants to risk trouble by keeping something that is no longer legal, whether it is a book or anything else.”

He added, “We are ordinary people. These shops are our livelihoods, and we don’t want to destroy them ourselves.”

Sumantra Bose, a professor of international and comparative politics at Krea University in Andhra Pradesh, India, has focused on the conflicts of the Indian subcontinent, particularly Kashmir, since 1993.

“My initial reaction was disbelief, but I quickly adjusted to what happened,” he told us. “It is a surreal blend of Orwellian and Kafkaesque in real-life form — like George Orwell and Franz Kafka combined. I felt that the people behind the ban have descended to the lowest steps even by their own abysmal and terrible standards.”

Cultural Erasure

Libraries in Srinagar and local bookstores now show empty shelves where the banned books once sat. In private homes, students and teachers read covertly, sharing PDFs and photocopies through encrypted chats.

Dr Hafsa Kanjwal reflected on the scale of the response and its contradictions:

Increasingly, as the days have passed, I have found myself puzzled by the attention this ban has received, from both international and Indian media. There is quite an outcry; people are talking about it on social media. What surprises me is that there have been book bans in Kashmir before. Earlier this year, books associated with Jamaat-e-Islami were banned, their copies seized, and homes searched — but there was far less public uproar. For me, what stands out about this current ban is the attention it has gained because the list includes several internationally recognized and well-known authors and writers. It raises a striking question: how can authorities justify silencing these voices?

While Kashmir’s conflict is unique, the ban is part of a global pattern: Authoritarian regimes frequently start by controlling the stories told in schools, universities, and libraries.

In Turkey, Kurdish literature faces censorship and systematic destruction. Hungary’s history curricula have been rewritten to glorify the nationalist state while suppressing inconvenient truths.

Sumantra Bose argues that since 2019 there has been a deliberate attempt by the ruling dispensation in New Delhi, with incremental support in Jammu and Srinagar, to rewrite the narrative of Kashmir. He believes that not only his own work but all twenty-five titles on the banned list interfere with this project of rewriting the Kashmir narrative.

“This effort aims to ensure that the narrative reflects only the exclusive ‘Hindu nationalist view’ of the Kashmir conflict and its agenda,” he says. “This agenda has been very clear since 2019: to erase the pluralistic aspects of the Kashmir conflict and reduce it to a simple question of law and order, governed by a very chilling variety of bureaucratic rule.”

Stakes Beyond Kashmir

For Kashmiris, the erasure is personal. It threatens to replace a plurality of perspectives with a single state-sanctioned narrative. For the global left, it is a warning: the first step in hollowing out a democracy is often the erasure of the past.

“Books carry knowledge, but they also carry memory. Removing them is not neutral; it is an ideological act intended to shape thought and identity,” a Srinagar resident inside a bookshop told us.

“When a generation grows up without access to critical histories, the state’s version becomes reality. And in that vacuum, dissent is delegitimized, and authoritarianism flourishes,” she added before slipping away.

Despite the raids, resistance persists. PDFs circulate online, the books remain available on e-marketplace platforms like Amazon and Flipkart, and discussion groups gather in private homes. In a city where fear is constant, these acts of reading and sharing are themselves defiant gestures.

Weeks after the raids, the banned titles were gone, leaving noticeable gaps in their shelves. In their place appeared volumes celebrating the state’s integration of Kashmir.