The Strange and Wonderful Subcultures of 1960s New York

Before planners and property developers turned Manhattan into a sterile playground for the wealthy, it was the site of extraordinarily creative art and music scenes. Critic J. Hoberman shows us how New York thrived in the shadow of nuclear war.

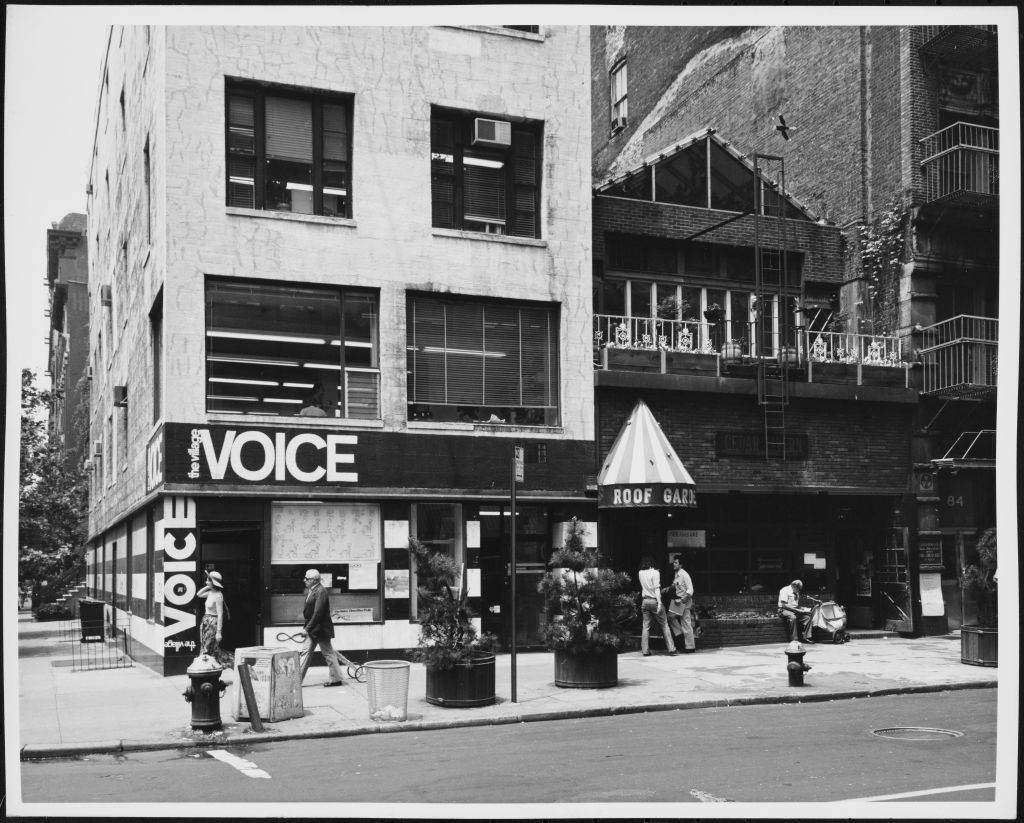

The former Village Voice offices, here photographed circa 1975, were situated in the heart of Greenwich Village, at Sheridan Square, New York, New York. (Edmund Vincent Gillon / Museum of the City of New York / Getty Images)

For fifteen years New York City — and specifically Manhattan — was understood to be the Prime Target and hence Ground Zero in a nuclear war. “The intimation of mortality is part of New York now,” E. B. White wrote in 1949; it was present “in the sound of jets overhead, in the black headlines of the latest edition.” Children entering kindergarten were issued dog tags. (I was one.)

Ruins were already present. Since the end of World War II, huge chunks of Manhattan had been leveled in the name of urban renewal, the new term for “slum clearance.” Buildings, entire blocks, even whole neighborhoods might disappear as if overnight, often rebuilt in the form of brutalist public housing projects. Many of these were on the Lower East Side.

Breaking Eggs

In the 1950s, a red brick palisade of high-rise public housing went up along Avenue D. Many Lower East Side residents, arrived since the war, were Puerto Rican; the area’s remaining Jews were mostly concentrated in older, less monumental public housing south of Delancey Street. “They were tearing down block after block,” the artist Aldo Tambellini recalled. “It looked like a bombed-out area from World War II.” Tambellini found inspiration in the rubble: “I vividly remember a dismembered wall remaining standing from an old synagogue with a big mural of the Lion of Judah.”

Greenwich Village was more contested. There were plans to demolish the neighborhood south of Washington Square; the god-like master builder Robert Moses sought to extend Fifth Avenue through Washington Square. Although his “emergency road” was defeated, new apartment buildings sprouted, and renovated brownstones appeared among the dilapidated cold-water flats west of Sixth Avenue. The newly finished luxury development Washington Square Village was a fortress amid the tenements and loft buildings south of Bleecker Street — eventually to be cleared in favor of the three concrete slabs called Silver Towers.

During the summer of 1959, the Village Voice reported an outbreak of vandalism in the South Village, as well as violence: “Attacks by neighboring youths on beatniks, particularly Negroes, have occurred with disturbing frequency.” Art D’Lugoff, proprietor of the neighborhood’s largest music venue, the Village Gate — opened the previous year in a former flophouse on the corner of Thompson and Bleecker — saw local resentment in the epidemic of smashed windows. The South Village was increasingly “cosmopolitan” even as aggressive slum clearance facilitated the incursion of upper-middle-class housing.

Harlem and East Harlem had public housing projects. So did the area around Pennsylvania Station, not to mention Brooklyn and Queens or the Bronx, which Moses bifurcated with two colossal expressways. Few of these developments were as ambitious as the Lincoln Square Renewal Project, which despite four years of community resistance obliterated the largely Black and Puerto Rican neighborhood of San Juan Hill to create space for the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

“You cannot rebuild a city without moving people,” Moses explained at the May 1959 groundbreaking, an event attended by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and that was deemed sufficiently significant to broadcast live in New York City classrooms (or at least mine). “You cannot make an omelet without breaking eggs.”

Free-for-all

Around one o’clock on a Sunday morning in early January 1961, the fire department shut down the Gaslight Poetry Café … again. Not six months earlier, the Village Voice ran a page-one story ominously headlined GASLIGHT, BEATNIK SPA, EXTINGUISHED FOREVER. The place was eulogized: “Poetry, singing — and an occasional brawl — made it famous.” Sick of the tumultuous neighborhood the South Village had become, owner John Mitchell threatened to move to the Caribbean.

South of Washington Square and east of Sixth Avenue, Greenwich Village was a territorial free-for-all. Urban planners and real estate developers joined forces to fight a tenuous coalition of neighborhood activists and night-life entrepreneurs like Mitchell and Art D’Lugoff.

On another front, the latter were themselves pitted against the police and other municipal authorities (including the Mob) who had allied with the community’s indigenous, working-class, largely Italian families in opposition to the burgeoning Beat element (drawn to the South Village by relatively cheap rents and relaxed social mores). Paradoxically, the Beats were united with their hostile neighbors in disdain for the swarm of weekend tourists courted by the coffeehouse entrepreneurs.

Race was also a factor. “The general resentment the locals felt toward the white bohemians was quadrupled at the sight of the black species,” Amiri Baraka recalled in The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones. Interracial couples drew hostile stares. Black and Italian teens repeatedly scuffled in Washington Square. During the summer of 1960, the Voice had articulated fears of a full-scale “rumble” in the park. Izzy Young told the press that “some people don’t want Negroes down here.”

The socialist journal Dissent was preparing a special-issue portrait of New York. “The biggest change in the composition of the Village beat scene and in Village life generally, is the far greater absolute number and far greater percentage of Negroes,” the sociologist Ned Polsky declared in his contribution.

Although the Village was scarcely easier for African Americans to rent apartments in than other white neighborhoods, the area was home to some notable Black writers, including Lorraine Hansberry, Claude Brown, and James Baldwin, as well as James Farmer, who had coined the term “Freedom Ride” while serving as the national director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the most prominent of New York civil rights organizations.

The Village was also populated by white supporters of civil rights. In the spring of 1961, NAACP organizer Medgar Evers addressed one of the several rallies held in Washington Square near the Judson Memorial Baptist Church, where the socially progressive new minister, Rev. Howard Moody, was pleased to officiate interracial weddings. In 1960, the Village Gate hosted several benefits for CORE as well as a regular Sunday night “Cabaret for Freedom.”

Coincidentally or not, the Gate was repeatedly cited by the NYPD Cabaret Bureau for dimming its lights during performances. Interviewed by the Voice, D’Lugoff wondered “why should a non-syndicate enterprise in a syndicate-ridden business be faced with perpetual harassment by the Police Department … They are trying legally to drain me and get me out of business. We are treated like criminals.”

Battle for the Village

The battle for the Village had been joined in the mid-1950s. The blocks around Seventh Avenue and Sheridan Square, where the Village Voice had its office, had been the neighborhood’s prime entertainment zone. But as the Italian espresso caffès transformed into Americanized coffeehouses, the tenement blocks south of Washington Square proved a magnet for Beat poets, folksingers, and all manner of stand-up extroverts.

The blind composer-musician Moondog worked the street. The freakish ukulele-strumming, falsetto-voiced Tiny Tim was a favorite at lesbian bars. Brother Theodore (last name Gottlieb), a German-born concentration camp survivor, introduced an element of Weimar Berlin to the scene with his sardonic audience-baiting rants.

Tourists followed. Weekends were hell. Outer-borough kids clogged the sidewalks. New Jersey cars cruised the narrow streets. In vain the police attempted to enforce a Sabbath Law: “If religion is demanded on MacDougal Street, I insist on it for Forty-Second Street,” Izzy Young told the Voice.

Beneath the festive banner hung from a second-floor fire escape, the Gaslight sold dishwater espresso and provided free entertainment. A bit more than a year after it opened, Mitchell’s coffeehouse got national attention when newsman Mike Wallace used the 116 MacDougal stoop as a location for a TV report on the Beats. By the summer of 1960, the Gaslight was a home for poets turned hip raconteurs, including the joint’s “entertainment manager” Hugh Romney (later the hippie-jester Wavy Gravy) and the jazz drummer turned stand-up comic Steve Ben Israel (soon to join the Living Theatre), as well as apostles of the folk revival.

Poets read for free. The musicians who initially served to clear the house expected to get something. One step up from busking, the Gaslight was a “basket house,” a venue that paid the talent from the money audience would pitch in at the door. When a cover charge was established, some were paid by the week, although conditions did not necessarily improve.

Even dressed up with some hanging imitation Tiffany lamps, the place, according to its frequent performer and eventual manager, Dave Van Ronk, a bearish, Brooklyn-born twenty-four-year-old high school dropout, was “hopelessly filthy” — a rat- and roach-infested tenement basement.

Summer 1960, the Voice ran J. R. Goddard’s three-part series on MacDougal Street’s “fruitcake inferno.” Café Bizarre was furnished like a spook house with flying bats and black drapes. The poet Ray Bremser’s wife Bonnie worked there as a waitress: “Everything about it was gross, intentionally grotesque and designed to hustle tourists.”

It was also a firetrap, she recalled, “always packed and very hot.” The management sent its provocatively ghoulish waitresses walking in the neighborhood — bleached hair, dead-white make-up, heavy eyeshadow, garish sarapes draped over purple leotards.

Beatnik Protests

South Village residents were agitated not only by tourists and visiting teenage hordes but also by publicity. Incredibly, the Coffee House Association hoped to institute an annual Mardi Gras — the theory being that, given “the school-integration situation,” New Orleans had lost its luster as a vacation destination — and thus drive the locals crazier.

The fire department closed the Gaslight for the first time less than a month after the Wallace interview. The police had determined that, liquor or no, coffeehouses were cabarets. Some blamed the striptease joints on West Third Street for the escalating anti-coffeehouse campaign. Others suspected that Carmine DeSapio, the recently defeated Democratic Party boss, long suspected of Mob connections, was attempting to shore up his neighborhood base.

“The shops selected were of course non-Italian,” Polsky noted in his essay, “although hardly any commercial establishment within blocks of the area doesn’t have fire violations.” The Gaslight and Café Bizarre were particular targets and café operators filed suit, charging “resentment by local residents against the influx into the neighborhood of certain minority and racially mixed groups.” Mitchell was briefly arrested for riling up a crowd while jawing with the local fire chief, who later told reporters that he had planned to close Café Bizarre as well as the Commons (across MacDougal from the Gaslight) but backed down for fear of a riot.

After the Gaslight and Bizarre were shuttered for overcrowding, the New York Times reported a “beatnik protest.” Organized by Mitchell and Bizarre owner Rick Allman, leader of the self-serving Coffee House Association, some eighty demonstrators marched through the Village in pouring rain, pelted from the fire escapes with garbage and redundant water balloons.

Crossing Sixth Avenue and marching up West Tenth Street, the protestors besieged the local firehouse. There, the Bizarre’s current headliner, international songstress (and schoolteacher) Varda Karni, Israeli by way of Paris, led the group in an improvised version of the Depression-era union anthem “I Don’t Want Your Millions, Mister” that, referring to the fact coffeehouses did not sell alcohol, went “We Don’t Want Your Whiskey, Mister.”

The Great Blackout

November 1965 had been a month of utopian expectation. Not only did the Film-Makers’ Showcase present the New Cinema Festival, but New York elected a handsome young mayor even as the Great Blackout altered the city’s consciousness.

Not since the Kennedy assassination two years before had there been a comparable universal event. Yet, “far from creating a mood of dread, the power failure created a mood of euphoria,” the artist Robert Smithson would note. There was an inexplicable, “almost cosmic joy.” Others living downtown recall an unexpected solidarity, a festive energy, and a collective excitement.

People asked each other what was happening and what it meant. Richard Tyler materialized at Claes and Patty Oldenburgs’s new Fourteenth Street loft to explain that he had caused the power failure.

The Great Blackout created jubilation in Harlem. LeRoi Jones, now living uptown, called it a “special effect.”

Suddenly, at the corner of Lenox and 125th, a group of white people were being taunted and robbed. The police swung into action — saving white people is their second most important function after their most important function, saving white people’s property … Windows were getting smashed and commodities disappearing at an alarming rate.

That same November, the artists known as the “Park Place Group” opened a cooperative gallery on West Broadway, a block and a half north of Houston Street. The ground floor of a six-story loft building, previously the province of an electrical appliance store, it was a fantastic space. The rent for what New York Times reporter Grace Glueck called an “improbable” eight thousand square feet (including the basement) was, by one account, an even more improbable $100 per month.

The ten-member Park Place Group was evenly divided between sculptors and painters, although only one, Tamara Melcher, was female. Many, including Dean Fleming, Peter Forakis, Forrest Myers, Melcher, and Leo Valledor, came from the Bay Area; a number were graduates of the California School of Fine Arts. Fond of terms like space-warp, optic energy, and four-dimensional geometry, the transplanted Californians were relaxed regarding new technology and unafraid of retinal kicks.

Theirs was an inclusive counterculture. They read Scientific American, dug the futuristic architect Buckminster Fuller (inventor of the geodesic dome), and pondered media theorist Marshall McLuhan. Inspired by Ornette Coleman, another West Coast émigré, the artists expressed themselves through the marathon Free Jazz (or “no jazz jazz”) sessions held at their original home, 79 Park Place, a five-story loft building on the eastern edge of the condemned Washington Street Market.

Relics of a Lost World

The building, discovered by Fleming in late 1962, was — save for the ground-floor coffee shop Walter’s Cozy Corner — entirely empty. It was owned by Columbia University and slated to be razed along with the market. (Produce would henceforth enter the city via the new Hunt’s Point market in the Bronx.) In the meantime, entire floors, approximately twenty-five hundred square feet, could be rented for $35 a month. Fleming told his friends.

The Group’s most prominent member was Mark di Suvero. Recovering from a spinal cord injury suffered in a freight-elevator mishap two years before, di Suvero could no longer fashion the heroically scaled arrangements of wooden beams scavenged from wrecked buildings that made his reputation. Yet he persevered, his grit an inspiration to younger artists.

Di Suvero was also a socialist. He hated Pop Art and — having severed ties with his dealer Dick Bellamy, whose uptown Green Gallery had brought James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol, and Tom Wesselmann to Fifty-Seventh Street — enthusiastically joined in a cooperative enterprise.

Spring 1963, a few weeks after Henry Flynt, Tony Conrad, and Jack Smith picketed the culture palaces, six months before the No!artists had their first uptown show, the Park Place Group turned their building’s fire-damaged fifth floor into an exhibition space. Like those at the March gallery, Park Place shows were collective environments; like the No!artists, the Park Placers took an adversarial position, but with a difference.

“We were having fun and not letting them be part of it,” Fleming recalled. To see the show “you’d have to go up five floors in the dark with the rats jumping, shit happening [and] once in a while, we’d put up a light bulb.”

Reviewing a Park Place exhibition in December 1963, the critic and sculptor Don Judd (having his first solo exhibition at Green that month), noted the Group’s stated opposition to the market and dislike of Pop Art. Once, but no longer, a supporter of di Suvero’s “thunderous” work, Judd professed surprise that the Park Placers were not di Suvero clones.

The group lost their lease the following spring, leaving the neighborhood as a monument to itself, an urban graveyard documented by a few stubborn artists. Danny Lyon’s 1967 photograph shows 79 Park Place boarded up and standing alone, a solitary tombstone on an otherwise empty block. Lyon, a twenty-five-year-old former photographer for CORE, was a friend of di Suvero, to whom he would dedicate his book The Destruction of Lower Manhattan.

Lyon’s pictures were relics of a lost world: “The silence left in the streets was startling,” he would later write. “As one wanderer put it, everyone left one night, even the dogs and the rats.”

The tectonic shift called “urban renewal” displaced artists throughout Lower Manhattan.

In the late 1950s, master builder Robert Moses suggested that David Rockefeller and other financial titans develop the old city below the Brooklyn Bridge and west to the Hudson. By the time the Park Place Group got their building, the painters once clustered at Manhattan’s southern tip, Coenties Slip, were largely gone.

Everything Is Now

The area around the Fulton Fish Market was also under development, although di Suvero was able to hold onto his studio. Lyon, who found a nearby place on Beekman Street, photographed di Suvero’s atelier as well as an abandoned artist’s loft four blocks away on Ferry Street in New York’s still smelly wholesale leather district once known as the Swamp.

Also on Ferry Street, Ken Jacobs occupied a small loft — the top floor of a six-story building two blocks from the Brooklyn Bridge’s Manhattan landing — which he managed to keep long enough to shoot a lyrical allegory, The Sky Socialist. The film was, of necessity, made on eight millimeter — Jacobs’s sixteen-millimeter camera had been stolen in 1964. After the city gave Jacobs and his wife Florence Karpf $1,600 to clear out, the couple found a loft on Chambers Street, across City Hall Park but close enough to continue filming Ferry Street and environs.

Where The Destruction of Lower Manhattan is brusquely apocalyptic, The Sky Socialist is tenderly elegiac — a paean to the Brooklyn Bridge and love letter to the artist’s wife. Largely confined to ancient rooftops and empty cobblestone alleys, the movie is silent and essentially gestic. The contemplation of eccentrically dressed actors hanging out amid fetishized props in a deserted urban landscape, its mise en scène is more understated than but not unrelated to that of Oldenburg’s early Ray Gun productions or Jack Smith’s orgiastic films.

The mood is shabby and bucolic. Ferry Street’s weathered walls, water towers, sooty metal shutters, and ancient brick cobblestones provide an abandoned city in which Jacobs suggests more than stages a triangle involving Anne Frank (Karpf), miraculously spared; Jacobs’s alter ego Isadore Lhevinne (Dave Leveson), an obscure writer whose 1931 novel of the Russian Revolution, Napoleons All, Jacobs discovered in a used bookstore; and Maurice, a manic sharpie in a Panama hat (filmmaker Bob Cowan).

Maurice functions as a creepy reality principle, lackadaisically mocking the oblique courtship of demure Anne and wistful Isadore: He presents her with various junk treasures, she hands him a glass of clear water that acts as a lens while, plugged into a transistor radio, Maurice dances by himself. Occasionally visited by the Muse of Cinema (Julie Motz), who ultimately supplies a happy ending, the characters bask in the sun or slip into reveries.

For all the references to historical tragedy, The Sky Socialist is a movie about the beauty of things as they are. The artist casts a glance; the sparse narrative is put on hold so the camera can ponder the grandeur of the bridge, the proximity of the East River, the caverns created by the arched municipal buildings, the top of the tombs, the clerks spending their lunch hour on park benches. All action is digression; everything is now.