Diego Rivera’s Resolute Socialism Is on Full Display in His Mural Pan American Unity

Diego Rivera was a champion of the socialist cause who sought to produce art that “belongs to all mankind.” Nowhere was this vision more clear than in his mural Pan American Unity, a homage to Hollywood, Mexican culture, and modernism.

A section from Diego Rivera's Man, Controller of the Universe, depicting Leon Trotsky, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Marx. (Wikimedia Commons)

Diego Rivera painted Pan American Unity for the 1940 San Francisco World’s Fair in an airplane hangar, accompanied by an armed guard. Shortly before he commenced work on the mural, his wife — the artist Frida Kahlo — and Leon Trotsky began an affair. Though Rivera remained an admirer of the hero of the October Revolution, he expelled Trotsky from his home in Mexico. The security budget required to protect the former military leader had already been putting a strain on the household’s finances. This was the last straw.

Pan American Unity features no image of Trotsky. Stalin appears on the painting’s fourth panel as one set of a triad of ghouls cloaked in a gray ether, alongside Hitler and Mussolini. They are surrounded by portraits of actors, chief among them Charlie Chaplin, who assumes a number of his satirical personas. A single arm, tattooed with a swastika and holding a dagger tightly, emerges out of the cloud, but it is held at bay by another, much larger, arm draped in an American flag and flanked by bombers and paratroopers. This is Rivera’s ode to anti-fascist Hollywood.

Since July, Pan American Unity, the artist’s single largest work, has been on display as the star attraction of the San Francisco MOMA’s (SFMOMA) Diego Rivera’s America, which runs through January. The exhibit offers canvas paintings from the 1920s and ’30s alongside murals, including two earlier ones completed in San Francisco, and a handful created in Mexico, which are projected as videos on the galleries’ walls.

Evinced in Pan American Unity is Rivera’s attempt to forge a hybrid art of the Americas alongside a post-Stalinist political unity. On the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution the artist had visited the Soviet Union with hope, but some criticism too. In the end his window into Stalin’s Russia turned him off; he began taking commissions from wealthy patrons in the West. In place of Stalinist doctrine, the mural portrays a carnivalesque unity between North and South American innovation, held together by the culture of the pre-Columbian civilizations in the Valley of Mexico.

Palaces and Temples

Rivera was born in 1886 to a middle-class family in Guanajuato, a city in central Mexico. His twin brother died before his second birthday. Fascinated by military strategy, trains, and technology, Rivera painted from a young age. This embrace of modernity was always alloyed to a close connection to indigenous culture. For him, the indigenous culture of Mexico was one in which art permeated all levels of society:

In the pre-Hispanic world everything in the life of the people was artistic, from the palaces and temples which remain monumental works of sculpture — with their magnificent frescoes that amaze everyone peering at them in the jungle — down to the humblest everyday pots, the children’s toys, and the stones used to grind grain.

As a teen, Rivera studied at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts, winning a bursary to travel to Spain. There he painted landscapes and still lifes, came to love Manet and Velázquez, and imitated El Greco. Between the travel scholarship and his first fresco commissions in Mexico, Rivera was a product of the public funding of art.

Collective Art

In Europe he honed his technique. After his bursary finished during World War I, he lived in Montparnasse, in the south of Paris, learning pointillism and Cubism while surrounded by the leading lights of twentieth-century modernism. On one occasion, Rivera accused Pablo Picasso of stealing one of his Cubist motifs; the maestro concurred silently by painting over the offending canvas.

But even in this vibrant milieu, Rivera grew dissatisfied with what he felt to be its stifling ideas about art. In particular, two decades before Picasso had completed his Guernica painting, Rivera bristled at what he saw as the Cubists’ hostility toward forms of representation that could accommodate narrative. Butting heads with Picasso’s wing of the movement, he attempted to carve out a path for himself that could express the tumultuous history being made around him.

One night at dinner, debate between rival artistic factions grew violent. An argument started in a restaurant on the Quai des Grands Augustins and spilled over into the apartment of Rivera’s comrade, André Lhote. It escalated further when a young poet, spewing the main group’s orthodoxies against “literary Cubism,” called Rivera and Lhote’s work derivative. Rivera slapped him and a fight ensued, during which the poet threw himself at the artist and pulled his hair.

After l’affaire Rivera, as this incident came to be known, the Mexican artist drifted out of the trendy cafe circles and came to view Cubism as a cult of personality. Aesthetically untethered, he moved toward Cézanne’s “constructionism,” which could accommodate the storytelling necessary for Rivera’s future frescos. His return to realism, wrote one critic, was “like watching a man focusing his eyes after an extended period of blurred vision.”

Under the influence of art historian Élie Faure, Rivera considered art movements as swinging between individual and collective epochs. Though neither Faure nor Rivera was religious, the former spoke of medieval churches as the grand achievement of the last period of collective art. European cathedrals were not merely houses of worship, he argued, but public markets, meeting places, the Greek agora — a dance floor and a place for ceremony.

Foreseeing the rise of steel buildings, Faure encouraged Rivera to explore fresco as an artform capable of accommodating this massive expansion of the built environment’s scale. Faure saw in this transformation of the skyline a model of modernity that could improve the lives of everyday people. These words stayed with Rivera on his pilgrimage to Florence. There he set out to examine the great Italian frescoes before returning to his homeland to forge a truly Mexican art, before taking his famous commissions in the north.

The 1930s: San Francisco and Detroit

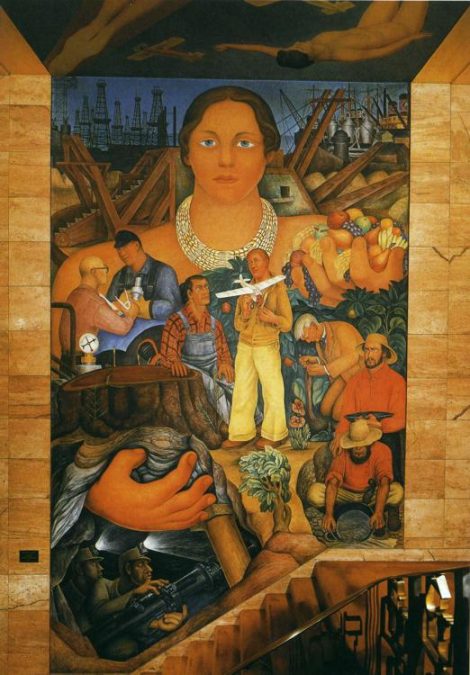

While painting the Allegory of California (also part of the SFMOMA’s current video exhibition) on an upper floor of the San Francisco Stock Exchange, now the City Club, Rivera was struck by the beauty of the city and the generosity of its inhabitants. He made friends, and presented solo shows in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

By February 1931, he’d finished the cheerful mural with an enormous, mythical, blue-eyed earth mother at its center, modeled on tennis champion Helen Wills Moody, with whom Rivera had an affair. This figure bears a cornucopia of California fruit in her left hand, while with her right, she lifts the earth’s cover to reveal soot-covered miners in terrible conditions clamoring for California gold and other metals. During this time the couple raced around the city in Moody’s two-seater Cadillac, with the six-foot Rivera crammed in the tiny dicky seats of the car’s trunk.

Throughout much of their 1930s stay in California, Rivera and Kahlo lived on Montgomery Street in San Francisco, near North Beach. There they befriended the Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange and were swarmed by (mostly Rivera’s) fans. “The poor guy can’t even go to the bathroom in peace because they’re bugging him all day,” Kahlo recalled.

They also met the art historian Wilhelm Valentiner of Detroit’s Institute of Arts. From their endless conversations on technology emerged another brilliant grand-scale US commission, the Detroit Industry Murals. In preparation, Rivera spent months studying the Ford Motor Company’s assembly lines on the city’s Rouge River. “Marx made theory . . . Lenin applied it with his sense of large-scale social organization . . . And Henry Ford made the work of the socialist state possible,” he remarked with admiration.

Even though he saw the socialist uses to which Fordism could be put, he also saw its limitations. In the real Ford factory, he found predominately white male workers. On his canvas Rivera integrated the factory floor, depicting black and Latino workers alongside the white ones, and devoting a panel to the women who mainly sewed upholstery in the factory as well.

At the time, Ford also manufactured planes, and in a tally of the pluses and minuses of modernization, Rivera depicted aircraft on one panel being used humanely to transport mankind and spark industry. On another panel, in contrast, he painted war planes with pilots in protective suits dropping bombs on innocent bystanders. The trick is repeated in another scene in Rivera’s fresco. In one panel a factory line produces cures while on another alien-like workers in protective masks fabricate mustard gas and organisms for warfare.

Easily one of Rivera’s finest works, the mural features machines morphing into robots, sci-fi comic-book killers, and (if you squint) Aztec gods. At the heart of Rivera’s image is a mechanical object equal parts Ford-factory assembly line machine and Coatlicue, the Aztec earth goddess. Its muted colors suit the Motor City’s palette — grays, silvers, and gleaming blues drawing the eye across metals and crowds. Apart from a sign added later, deploring Rivera’s “reprehensible politics,” the artist was allowed to paint as he pleased in Detroit.

Man, Controller of the Universe

New York was another story. For Rockefeller Center’s RCA building, patriarch John D. Rockefeller Jr. chose a theme that was comically grandiose: “Man at the Crossroads Looking with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future.” Rockefeller wanted viewers to reflect on the state of the world as they walked past the mural, which was intended for the lobby of a building that he was also trying to fill with Depression-era renters. Rivera was not the Rockefellers’ first choice, but neither Matisse nor Picasso was free.

Rivera managed to earn the commission by charming the family during long, friendly dinners where he admitted that he planned to contrast capitalism and socialism in the mural. But he also obscured a detail in the blueprints, a portrait of Lenin. When Rivera’s assistant Lucienne Bloch worried the mural was veering too far left, Kahlo calmed her. Every night, she said, Abby Rockefeller (John Jr.’s wife, and Rivera’s patron) climbed the scaffolding and nodded with approval.

But as its unveiling neared, Rivera snuck in the offending face, who links the hands of black and white workers. Diplomatically, John Jr.’s son Nelson wrote to Rivera, pleading for an alteration: “I noticed that. . . you had included a portrait of Lenin. This piece is beautifully painted but it seems to me that his . . . appearing . . . might very easily seriously offend a great many people.” After politely refusing to remove Lenin, Rivera was paid his fee of $21,000 (around $450,000 today) and escorted from the lobby.

“All art is propaganda,” Rivera quipped. “The only difference is the kind.” The Rockefeller family, whose fortunes had been made over the dead bodies of striking workers out west, knew this, but thought they could, nevertheless, purchase Rivera’s vision. “Since art is essential for human life, it can’t just belong to the few. Art is the universal language, and it belongs to all mankind . . . I want to use my art as a weapon.”

In the end, the Rockefellers veiled and then painted over the fresco with a more patriotic American allegory, effectively destroying Rivera’s work. The great loss to New York City art was Mexico’s gain. From photographs his assistant surreptitiously took, Rivera recreated the mural in 1934, renaming the Mexican version Man, Controller of the Universe.

San Francisco Again

In creating Pan American Unity six years later, Rivera proclaimed that he was in search of “a real American art . . . From the South comes the Plumed Serpent, from the North . . . the conveyor belt.” But before starting on the commission, Rivera busied himself helping Trotsky apply for asylum from the Mexican government. Having made preparation for Trotsky’s arrival, Rivera fell ill and left the job of picking up Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova to Kahlo. When the revolutionary landed, Rivera and Kahlo put him up in their home, Casa Azul.

Soon mutual admiration bloomed into an affair between Kahlo and Trotsky. The revolutionary passed notes to Kahlo in books he lent her, “sometimes under Rivera’s nose.” But when Rivera discovered the affair he presented Trotsky with a large skull made of sugar and bearing Stalin’s name. Though not amused, Trotsky failed to draw the connection between the artist’s symbolism and the affair. This latest bout of infidelity would lead Rivera and Kahlo to divorce.

By the time Ramón Mercader buried an ice pick in Trotsky’s skull in August 1940, Rivera was on a San Francisco scaffolding painting his single largest mural. Fearing Stalin’s cruelty more than ever, Rivera painted under armed protection before an audience for four months, reveling in the limelight. Soon the couple reconciled, and Kahlo joined him in San Francisco, where they remarried. While she convalesced from hip and spine treatments, hundreds of thousands of Californians came to see Rivera’s mural.

Unveiled in a special SFMOMA gallery with no fee for entry, the mural features dizzying panoramas of burnt sienna matching the Golden Gate Bridge, stretching next to prolific commissioning-architect Timothy Pflueger’s prominent skyscrapers in the city’s skyline; jade-blue and turquoise swaths of the San Francisco Bay and the Pacific; Mount Shasta; and the deserts of the Valley of Mexico. On the leftmost panel, Olmec, Toltec, and Aztec pyramids sprawl above a blue-caped Nezahualcoyotl — a philosopher, scholar and poet-king of fifteenth-century Texcoco, the Athens of pre-Columbian America. According to legend, Nezahualcoyotl invented a flying machine long before the Wright Brothers.

The second panel mirrors the fourth (which depicts the trio of Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin painted with the aim of lobbying the United States to join the war effort). But rather than criminals, as in the fourth, this second panel depicts a revolutionary tradition led by Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Simon Bolivar, Miguel Hidalgo, José María Morelos, and John Brown.

At the centermost panel is the Ford machine/Coatlicue from the Detroit mural, but now fleshed out as a goddess on the left side and a metallic machine on the right. Rivera is suggesting Mexico and California are one land, one people, which was literally true before US annexation in the 1840s. Underneath are Kahlo, Rivera, and their San Francisco friend, the actress Paulette Godard, planting a ceiba tree, symbolizing “closer pan-Americanism.”

At his best, Rivera embodies a stupendous modernist vernacular that sits between the instruction manual and the Old Masters. The intricacy of Pan American Unity’s colors alone makes the fresco’s nearly two decades in cold storage a true shame — another of the Cold War’s petty crimes against culture. The mural’s patron, architect Pflueger, died in 1946, and it was stored until the world war’s end might produce funds to mount it. In 1961, it was mounted in City College San Francisco, twenty years after Rivera completed it.

Though its detractors include many who directly called for its destruction or disappearance, as Rivera’s largest single work its scale alone is a marvel, never mind its diplomatic and political ambition. On the canvas, Rivera succeeded in reframing the civilization of the American West and Mexico, linking together progressive political movements and artistic innovations — from Mexican independence to US abolition of slavery to anti-fascist Hollywood — by creating a mythological origin for them in Texcoco and the Aztec people.