Richard Pryor Wasn’t Just a Brilliant Comedian — He Was a Trenchant Social Critic

Richard Pryor revolutionized stand-up comedy with his sharp wit and deeply personal monologues. He also held up a mirror to US society, revealing its brutal realities of inequality and racism.

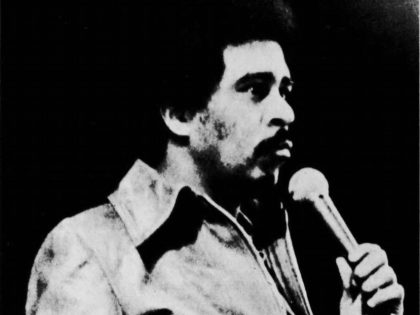

Richard Pryor in the 1970s.

- Interview by

- Sasha Lilley

Richard Pryor, who died in 2005, may be the greatest comedian the United States has ever produced. He transformed the medium, making it intensely personal and political, turning his caustic wit on racism, injustice, and himself.

Scott Saul’s book, Becoming Richard Pryor, is a deeply researched account of the author and comedian’s formation, both personally and socially. Saul, a historian and professor of English at the University of California Berkeley, interviewed more than eighty of Pryor’s family members and friends and dug up hundreds of documents that together help paint a picture of the world Pryor came out of and the world he helped shape.

In an interview several years ago on the California-based progressive radio show Against the Grain, radical journalist Sasha Lilley spoke with Saul about Pryor’s formative years in the segregated Midwest and the efflorescence of his art during a time of left-wing politics. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did Richard Pryor revolutionize comedy?

He was fearless about what could be talked about onstage. He went into the deepest and darkest places of his own experience and psyche. And not only was he going to talk about his intimate life, he was going to think about how his intimate life was shaped by politics. He’s going to talk about abuse in sexual relationships between men and women. He’s going to talk about police violence and police harassment. He’s going to talk about the atrocities of our national life and the violence in it.

It’s hard to think of a comedian that follows Pryor that isn’t indebted to him for opening up a space and allowing stand-up comedians to occupy a much bigger place in the culture.

He was a great physical comedian. He was a great storyteller. He was a great joke-teller. You can learn from him as a craftsman as well as a social critic.

Pryor grew up in Peoria, Illinois, and his grandmother ran a brothel and was a mother figure to him. Tell us about the world they inhabited in Peoria.

When Richard Pryor was born in Peoria in 1940, it was probably the most thriving “sin city” in the Midwest. People from Al Capone’s organization in Chicago would come to Peoria and have their minds blown. They couldn’t believe what was happening in the streets — open prostitution, open corruption, open gambling — with no interference from the law.

Richard Pryor’s grandmother moved to Peoria, sensing an opportunity, and set herself up in the red-light district. Through the ’40s, they had a pretty good livelihood because the sin city was protected.

He was growing up in a brothel. While it was protected in the sense that cops weren’t raiding it, it was still a very violent place. One of Pryor’s most intense memories as a child was waking up, hearing screams, and not knowing where they’re coming from and what’s going on. That’s a parable for his childhood. He never knew when the violence would descend. He never knew if he was going to bear the brunt of some of that violence.

His grandmother was, like so many of the people in his family, an incredibly complicated person. She was very forceful, but she could also be tender. He called her “Mama.” She’d beat him, but she was the closest thing he had to a rock — a very jagged rock — as he grew up.

Pryor came of age in the segregated 1950s Midwest. What was that like for him as he reached his teens?

Something changed in Peoria. During World War II, they had a base near the city. GIs were coming to Peoria and the red-light districts, spending their money in brothels. But they were also getting venereal disease in those brothels, and the United States federal government decided, “We don’t like this.” It was the beginning of a new reform coalition to stamp out vice in Peoria. As a result, by the ’50s, Peoria had rebranded itself as this all-American city.

They put a freeway through the old red-light district, so Richard Pryor’s whole family had to move. Peoria was only 3 percent black when Richard Pryor was born there. It was only about 10 percent black when he left, and he had to move to a very white part of town in the early ’50s. He went from being in this very interracial community in the red-light district to being on the front lines of integration efforts.

Pryor definitely lived in a segregated world. I think that’s one of the things that caused his ambivalence as a performer when he was facing white audiences. When he started coming into his comedy in sixth grade, he was performing for these kids, and they were laughing hysterically at his jokes and his funny pantomimes. But when he wasn’t onstage — when it was recess — a lot of the same kids were beating him up and calling him the N-word. He had to wonder, “Why is it they laugh at me when I’m performing and beat me up when I’m not onstage?” He knew that, with certain kinds of white people, laughter is a very complicated thing, and that it’s not simple being a comedian.

How did Pryor end up becoming a performance artist?

There were two different phases that illuminate this.

The first is that he found the Carver Center, the mecca of Peoria’s black community, when he was about fourteen or fifteen years old. He was taken under the wing of Juliette Whittaker, who was this angel in his life — that’s what he called her. She runs the drama guild, and there he first learns what it means to become an actor. She discovers that this boy has an insane amount of talent and that he can spin yarns like nobody else. She starts putting him in star roles and asking him to MC talent shows. So Richard Pryor is performing for a black audience for the first time, is MCing these talent shows, and gets a sense that, “I can do this. I can be the person at the center of it all.”

Unfortunately, after only about a year and a half at Carver, he is kicked out of school, and his dad basically says, “You’ve got to work.” He’s fifteen or sixteen years old, and he can’t go to Carver in the afternoon. He starts working at a series of desultory jobs. After a few years of working, he decides to join the army.

It’s a horrible match, and he’s kicked out of the army just as he was kicked out of school. When he comes back to Peoria, he decides that he’s going to be a performer. Suddenly, all those connections that his family had with the underworld are of great use to him because the same people who lived next to Pryor in that red-light district in the ’40s are running the clubs that have survived urban renewal. And they give him a great shot.

Richard Pryor eventually moved to New York’s Greenwich Village in the early 1960s. What was the scene in Greenwich Village like at that time?

It was effervescing in all kinds of ways. It was the era of pop art and “Happenings.” It was the era of Andy Warhol blowing up as a figure. There was off-Broadway and off-off-Broadway.

Pryor gets thrown into the emerging improv scene. Improv exercises had existed before, but The Improv, the club, starts just before Pryor arrives, and he finds this ragged band of individualists trying to become comics, very hungry for action. He goes to The Improv late at night and performs these improv games for hours and hours. A lot of it was about throwing yourself into scenarios and not knowing where you’re going to end up but being a good listener and being responsive.

I think this changed what he was like as a comedian. A lot of stand-up comedians are basically responding to an audience and have trouble segueing into acting. But Pryor, from an early age, was in dialogue with performers. He was good at being super sensitive to the possibilities of the moment and that dialogue.

Where did Pryor take his inspiration from, and how did he see himself fitting into the culture of black comedy in the early to mid-1960s?

The black comedians that most affected him were his grandmother and his father. They raised him. His grandmother was an incredible storyteller. His father was brutally honest, and a lot of comedy comes from that brutal recognition of a painful situation and making it so crystal clear that you can’t help but laugh.

In the ’50s, when he was starting, his models were coming from TV and film. It was Jerry Lewis and Sid Caesar. By the early ’60s, there were possible models for him to emulate like Dick Gregory, who was more political. But Pryor was more magnetized by the example of Bill Cosby, largely because Bill Cosby stood for success with a capital S: best-selling records; hosting the Tonight Show; eventually starring in his own TV show.

Pryor adopted some of Cosby’s rhythms when he was just starting out in New York City. But he could never really be a Cosby clone, because Cosby has that air of total confidence. Pryor was much more antic and gawky, and this sort of man-boy was his persona in that early stuff.

As the ’60s unfolded, how did Pryor see himself in relationship to the increasingly intense politics of that era?

Through the mid-’60s, Pryor was registering the politics of the decade as a person. He had relationships with other people who were active, and they’d talk about politics. But it wasn’t shaping his act in deeply consequential ways until around 1968.

At that point, he was part of the countercultural scene and getting more radicalized by Black Power circles. On the one hand, you have the zaniness of the counterculture, the love of the absurd, the critique of institutionalized religion and the institutional power of the state. He was doing these crazy riffs in the person of a figure of authority, like a minister who touches himself because he loves God so much and his body is his temple.

On the other hand, the politics of the Black Power movement were giving some trenchancy to what he was doing — it was giving that zaniness more of a point. In the late ’60s, he recorded his first album, which was titled Richard Pryor, and you see the edge of the late-’60s black politics merging with the “love the absurd” that you see in the counterculture. But it wasn’t quite the incendiary Pryor that we know from the ’70s yet.

A turning point for Pryor was in 1971, when he ended up in Berkeley, a city that was experiencing a very intense concentration of both the counterculture and radical politics. What happened to him during that period?

The three years before 1971 were the time of Richard Pryor’s double life. On the one hand, you have him trying to make it on mainstream TV. He was in Movie of the Week. He did an episode of The Partridge Family as a special guest star. But he was also getting drawn into these more political circles of the counterculture and Black Power, and he tried to make, for example, his own avant-garde movie that would have been like Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song or Putney Swope, but it was in shambles. He was doing too much cocaine. He didn’t have somebody to help him structure it.

By 1971, his marriage from the late ’60s had fallen apart, and he felt that the film he was trying to make is kaput and dead on arrival. In February 1971, there was a huge earthquake in Los Angeles, and he takes it as a some sign from God that this is not the place for him. So he comes to Berkeley without much of a plan for what he’s going to do.

It’s in Berkeley that he reinvents his act in deeply consequential ways, and he starts experimenting. He creates scenarios for a guerrilla film, he tries stream-of-consciousness poetry, he creates a sound collage, he does antiwar teleplays. It was like this artist trying to figure out, “What is my form? What is my medium?”

One thing he’s not trying to do is make people laugh. There’s a real search, with great artistic integrity, to find out who he might be and what message he’s trying to get out there. He’s been a comedian for over a decade at that point. He knows how to make people laugh. But he’s looking for something deeper.

While Richard Pryor was in Berkeley, the prison rebellion at the Attica State Penitentiary in upstate New York was violently suppressed. The prisoners had called for political rights and better living conditions, and when the prison was stormed on September 9, 1971, forty-three people were killed, mainly inmates. How did Attica affect Richard Pryor?

Attica and the suppression of that prison riot was so brutal, it shook him to his core. He was from a black working-class world. He thought of himself as somebody who, if he hadn’t found the stage, would be destined to be in prison. When he heard that all these black prisoners had been killed in the suppression of the prison riot, I think he felt like, “Those are my brothers who have been killed.” It made him feel like he needed to speak out about the atrocities on the American political scene.

He skewered without mercy those who he saw as responsible for the suppression of the Attica riot. And he had a lot of political insight, because the reason that riot could be suppressed in the way it was had to do with liberalism at that time. It was not just rock-ribbed conservatives who sent in the troops to Attica. It was Nelson Rockefeller, the liberal Republican. When he condemned Rockefeller, and when he condemned Russell Oswald, who was the New York prison commissioner, he was saying that liberalism is not the way to go and we need a more radical alternative.

After Berkeley, Pryor finds himself in a Hollywood. How did he navigate that world, and how welcoming was it to him?

He improvised his way to stardom. He was given very tiny openings, and he made the most of them in ways that are, to my mind, mind-boggling. For example, he leaves Berkeley, partly because he’s offered this part in Lady Sings the Blues by Berry Gordy, who is moving from Motown to thinking about Motown Pictures. It’s Gordy’s first big movie, and he wants to give Richard Pryor a walk-on part called “Piano Man.”

It’s supposed to be a one-line role, but Pryor starts riffing, and people love it. He develops his interplay with Diana Ross, who’s playing Billie Holiday. The producers and writers of the movie say, “We need this energy.” He basically improvises until he’s the third starring role in the picture and the death of Piano Man is the crucial event in the film.

That’s what he did again and again. He was given a tiny role, and he made it so much deeper and complex and entertaining.

One thing that I hadn’t realized was that Richard Pryor was one of the writers of the film Blazing Saddles.

There have been a lot of genre spoofs in Hollywood history, like Airplane and Top Secret, but very few of them have the intense political edge that Blazing Saddles does. Very few of them go to places that movie does. I went and looked at the original scripts, and you can see just how sharp that movie was when Richard Pryor was at the center of the writers’ room: so many deep jokes. He left his stamp on that movie.

Hollywood was going through a great crisis. There were no more films that could bring together the youth audience and the older audience. So they started to create these youth divisions to find a way to bring young people back into movie theaters. They gave a lot of power to people who would never have had the ability to greenlight a movie — people like Mel Brooks, who had just done The Twelve Chairs and The Producers, which were thought to be commercial bombs. He was allowed to create this new western spoof, Blazing Saddles.

The woman who gave Richard Pryor his first job as a star was Hannah Weinstein, who had been basically blacklisted in the ’50s and migrated to England. She came back to America, and when she started a film company here, who did she want to star in the lead? Richard Pryor. So it’s sort of the mavericks of the new Hollywood that were willing to bet millions of dollars on Richard Pryor and his wayward genius.

Richard Pryor went from these tiny roles to becoming the leading black movie star of the 1970s. Why do you think he was as popular as he was?

Richard Pryor has to be one of the most complicated and conflicted people to ever live. When he came onstage, there was this aggressive edge, where he was going to demystify the world and show you ugly truths about it. But he was also the most vulnerable of souls. He never had a real childhood as most of us would understand it. He was never allowed to flourish without having this threat of violence around him.

When you saw him onstage, yes, there was a real edge to his humor, but you always had a sense that he was critical of himself at heart. It wasn’t like he was just being aggressive, saying, “I am the one to show you these truths.” It’s actually, “I’m going to show you truths about myself because I am so imperfect.” That strategy was incredibly effective and dramatically powerful.

He could do a riff about police brutality, and there would be white and black people in the audience, and they would come to some mutual recognition of the problem through his act and hopefully could start to have a bigger dialogue as well, outside of the theater: Richard Pryor had said the unspeakable, and now more people can comment on it.

You chose not to cover the latter part of Pryor’s life in your book. Why did you decide that? And how should we remember Richard Pryor today?

I felt like the story of how he rose to become this incredible Hollywood star and this trailblazer who forever changed the rules of American comedy hadn’t been told or researched. I do talk about the latter half of his career in an epilogue, but to my mind, that’s where the story becomes very sobering. There’s already so much darkness in the tale I tell that I felt that was a better place for the balance to rest.

There are two things going on in my book. One is the story about a person who goes from blockage to blockage and keeps repeating himself and repeating his mistakes. Somebody who grows up around violence and then starts administering violence and beating people. It’s tragic how, even though he had so much perspective on the violence in his life, he couldn’t escape that cycle of violence. That’s one side of the book.

The other side is about how somebody like Richard Pryor, born in the margins of American life, made a way out. Who would have thought that this person, raised in a brothel in Peoria, would forever change American culture? By stopping most of my story in 1978, you get the sense of that, and of somebody opening things up. That’s where I wanted the stress to fall.

Among comedians, Richard Pryor is the great forefather, the great ancestor. But I think, for people who want to understand our world and laugh at it but also register its horror, he’s the person to go to.