The Woodcraft Folk Are the Socialist Boy Scouts

Unlike scouting groups like the Boy Scouts who promote jingoistic patriotism, Britain’s Woodcraft Folk are left-wing, coeducational, anti-militarist, and egalitarian. It’s the type of democratic, cooperative institution kids need.

West Oxford members at a peace demonstration. (Woodcraft Folk Heritage)

A 1975 semi-fictionalized film titled Our World: Woodcraft Folk shows a working-class British family of four — parents Pam and Jack and children Polly and Alan — out for a walk in the woods near their home. They catch a stray ball thrown their way and trace it to a nearby gaggle of children dressed in green Scouting shirts with colorful badges.

Their Scout leader, a friendly man with glasses, guides them in examining a gray squirrel’s nest and the local flora and fauna. The little boy, Alan, immediately runs off to join the group of Scouts, worrying his mother that her children are intruding on a private organization.

“That’s alright, love. He’s alright over here with us,” says the Scout leader. “We call ourselves the Woodcraft Folk.”

Unlike the leading gender-segregated Scouting organizations that promote patriotism, morality, and entrepreneurship, like the Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts, the Woodcraft Folk are the foremost left-wing, coeducational, anti-militarist, egalitarian Scouting organization in the world. A vital current in British society since 1925, the Folk lead the collective adventuring and skill-building of the Scouting movement in a way that embodies solidarity, empowerment, and sustainability, while consciously educating its young members in an anti-racist, socialist politics.

In the words of their 1925 charter:

The welfare of the community can only be assured when the instruments of production are owned by the community . . . when the production of all things that directly or indirectly destroy human life ceases to be; and when man shall turn his labour from private greed to social service to increase the happiness of mankind.

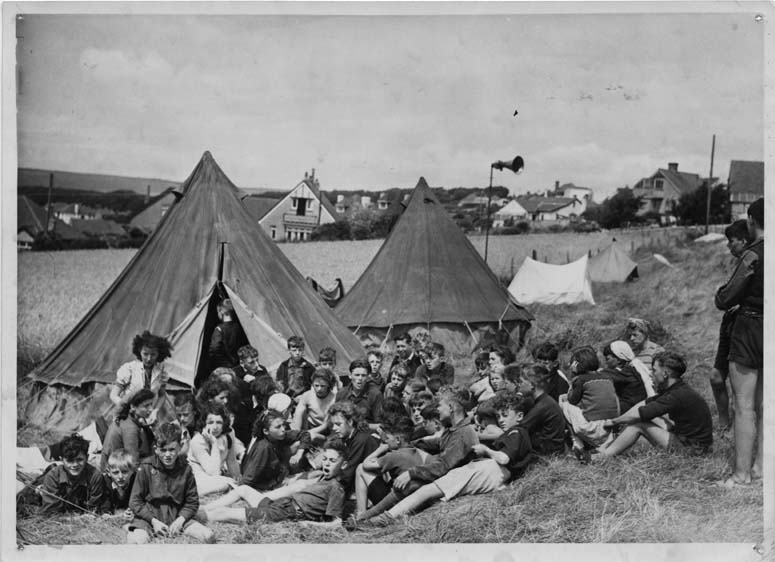

Concentrated in industrial cities and towns, Woodcraft Folk groups still meet weekly throughout the year to engage in outdoor recreation and cooperative play, learn about history and social issues, and develop an international outlook. The leadership and readiness of a Scouting movement can prove essential in times of crisis: the Woodcraft Folk were instrumental in the Kindertransport, the British effort to save almost ten thousand Jewish children from Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Poland before the outbreak of World War II. Many of the effort’s beneficiaries were their comrades in the Socialist International’s International Falcon Movement, a network of working-class children’s organizations that defiantly convened international peace camps as xenophobia grew ahead of the war.

The movement shows the vitality of a democratic and autonomous youth organization in the context of the struggle for a better world. Free from adults’ gaze, Woodcraft Folk are encouraged to exercise their creativity in the utopian social laboratories of movement summer camps.

Adult leaders and youth members are joined by shared goals and mutual respect — at least half of the movement’s trustees are under the age of twenty-five. The responsibilities of cooperative governance ensure that members develop organizing skills and democratic leadership practices that prepare them for lifelong engagement in social movements. And while the basic principles of the movement have remained steadfast for nearly a century, each new generation of Woodcraft Folk develops and refines the organization’s political priorities.

Scouting for a Better World

Returning to the old, slightly didactic but endearing movie, we meet our family again, a few days after their trip into the woods. They have decided to visit a Woodcraft Folk meeting at the local primary school. As they arrive, the Folk — again donning their green shirts — are discussing international bonds of family and friendship, and Polly and Alan are invited to join in some traditional Morris dancing.

Pam and Jack are invited to attend a meeting of Woodcraft leaders to learn more about the group. At the meeting, the leader reads from the constitution: “The Woodcraft Folk is a movement that unites children, young people, and all who are young in spirit. It seeks to direct the enthusiasm and energy of youth towards the transformation of our present troubled society.”

This sparks a debate among Woodcraft leaders: some believe that social change requires doing away with “the whole rotten system,” while others are more interested in “bringing about reforms more slowly and legally.”

This “political talk” makes Pam visibly uncomfortable: “I didn’t know the Folk was political — we wouldn’t have joined if anyone had said so, it’s for the children!”

A voiceover reiterates the movement’s objective to help children “make an early start in the struggle for a better life,” in which they will “notice the victims of oppression and clamor to help them, whether it’s in the black ghettos of the USA or in their own street.” The leader assures Pam that, rather than sectarian indoctrination, the Woodcraft Folk offer an education in global citizenship that will benefit children throughout their lives.

After mulling it over at home, Pam and Jack decide not only to enroll Polly and Alan in the Folk, but to volunteer as leaders themselves. Their entire family is transformed: where there had been malaise and alienation from limited social ties and too much of “the secondhand life of the square box” (television), there are now camping trips, sing-alongs, and international peace delegations.

As a result of her own political transformation, Pam confronts another mother outside the local school for making racist remarks about black families moving into their neighborhood. While it is maybe the film’s most painfully contrived scene, it reflects the potential of the Woodcraft Folk to transform the political consciousness of seemingly moderate families.

The family’s experience gets at the kind of progressive transformation that Woodcraft Folk has always hoped to effect. The organization was founded in 1925 by a group of teenagers in the multiracial working-class neighborhood of Lewisham. Nineteen-year-old Leslie Paul, an active member of the cooperative movement and veteran Scout, invited a few friends to meet in his mother’s backyard to launch a democratic, anti-imperialist, coeducational scouting organization.

Though Paul and his friends had grown up camping and hiking with the Boy Scouts, the devastation of World War I led them to reject what they saw as the scouts’ paramilitarism: “our brothers and fathers — many of them had been killed, so we were, as it were, the survivors, and we were now deeply troubled as a generation, and even an embarrassment about the Scout movement of which we had been part.”

Boy Scouts founder Robert Baden-Powell wrote Scouting for Boys, the Scouting handbook first penned in 1908 and republished continually since, out of concern that industrialization and urbanization removed young men from nature to the point that they would be underprepared to fight in imperial conflicts. The Woodcraft Folk founders, on the other hand, held a kind of nostalgia for preindustrial society, but one originating from a conviction that industrial capitalism had alienated the working class from their labor and social relations. Rather than using mountaineering and “woodcraft” skills to prepare young men to expand and preserve the British Empire, the Woodcraft Folk’s founders focused on helping working-class boys and girls collectively build a better world.

The Imaginative Worldmaking of the Folk

This was not Paul’s first attempt to build left-wing Scouting. At age sixteen, he set up a lodge of the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, an anti-militarist Scouting group (with what we would now recognize as a very unfortunate acronym) founded by former Boy Scout leader John Hargrave. When Hargrave disapproved of Paul’s initiative to use the Kibbo Kift group to coordinate activities between various cooperative and socialist groups in South London, Paul was dismissed from his leadership role for being a child. Hargrave’s insistence that leaders needed to be over the age of eighteen was part of a larger antidemocratic turn that eventually tore his organization apart, but Paul’s experience reaffirmed his belief in the need for youth to have their own democratically led movement.

The radical milieu of the trade union movement and the emergent Labour Party shaped the Woodcraft Folk’s stand against war, sexism, racism, and inequality. A 1926 pamphlet titled Who’s for the Folk? outlines the organization’s founding commitments:

The Woodcraft Folk seek to establish a new social order. They believe that when the worker achieves freedom from wage slavery and the fruits of the earth are garnered by the toilers, then will a new stage of development open out to man . . . We go out of the town and away to the hills and woods . . . After the ugliness and monotony of the smoky city we find new life among the green growing things and new health in the sun and the four winds. And this health together with our understanding enables us to fight tenaciously for the social betterment.

Rather than indoctrinating youth to fit into capitalist society, the Woodcraft Folk invites children to initiate lifelong practices of imaginative worldmaking to bring about social change.

As the Folk expanded across England, recreational activities — camping, hiking, cartography, birding, storytelling, handicrafts, and other traditional badge-earning activities — were supplemented with engagement in working-class politics. Woodcraft Folk demonstrated for a National Health Service and demanded a suite of social reforms including childcare, improvements in urban planning, labor protections, social insurance, and the abolition of police and military training and recruitment in schools.

The Woodcraft Folk played an instrumental role in supporting the Kindertransport, smuggling Czechoslovakian Jewish children into Britain by dressing them in Folk uniforms and sponsoring refugees in foster homes with Woodcraft Folk leaders. At the end of World War II, Folk groups purchased surplus parachutes from the British government, dyed them bright colors, and used them for both play and protest in an act of subversion of militarism.

Woodcraft Folk’s sustained emphasis on internationalism has led the organization to protest the Vietnam War, apartheid in South Africa, the war in Iraq, and the occupation of Palestine. The group continues to convene international peace encampments and exchanges with sister organizations through the IFM-SEI.

Despite a lack of formal affiliation, the Woodcraft Folk have always maintained a close relationship with the Labour Party. Impressed by the hundreds of Woodcraft Folk who turned out for May Day marches and general strikes, and overwhelmed by the prospect of large youth auxiliaries overwhelming local party operations, Labour Party leaders began encouraging youth children to get involved in Woodcraft Folk chapters in the mid-1930s. At the Woodcraft Folk’s ninetieth birthday celebration in 2015, Jeremy Corbyn was invited to ceremoniously cut the cake.

Honoured to help Woodcraft celebrate 90 years of Spanning the world with Friendship at their big gathering today! pic.twitter.com/QrEzqTh2Yj

— Jeremy Corbyn (@jeremycorbyn) June 13, 2015

A book marking the anniversary proudly states:

Woodcraft Folk is the only youth organization that states in its constitution that every adult and young person moving into the field of work should join an appropriate trade union. There is simply no other youth movement that recognises the deep importance of organised labour to such a degree

The Woodcraft Folk are a rare surviving youth organization from the early twentieth-century radical milieu of cooperative organizations, socialist Sunday schools, and other programs. While the Labour Party would come to move rightward, the Woodcraft Folk have definitively stood in the radical vein of British left-wing culture.

The organization of the Woodcraft Folk as a Scouting movement makes it a preserve for the special, developmental time of childhood that provides adventure, friendship, and fun, while orienting children into a movement for causes they will continue in as adults. As kids today are all too familiar with the contemporary crises of capitalism — climate change, high levels of stress and mental health issues, downward mobility and poor job prospects, segregation, police violence, and the suspicion and criminalization of young people of color and youth in general — we need venues that are youth-led and attuned to the autonomous development of young people.

Fashioning a New World

What might such a youth movement look like in the United States? The settlement movement founded programs for working-class children during the Progressive Era that focused on correcting social ills and assimilating youth into middle-class society rather than establishing a new social order. Camps along the “red summer belt” during the Popular Front offered radical working-class children and families opportunities for sectarian recreation, but only a few survive — notably, Camp Kinderland and Camp Kinder Ring, both affiliated with the Jewish labor movement. The Quaker American Friends Service Committee’s work camps in the 1940s proposed a reverse trajectory: sending suburban and rural youth to engage in cooperative practice in industrial towns and cities, rather than sending kids from industrial areas out to the countryside.

More recently, Bernie Sanders has demonstrated a strong commitment to children’s institutions, dating back to his days as mayor of Burlington, when he marshaled public support for a youth center that developed into an influential New England DIY punk venue. While my Students for Bernie chapter sometimes resembled a scouting group as we descended upon rural Iowa, electoral campaigns and traditional organizing models are more oriented toward achieving imminent goals than innovating practices of revolutionary joy.

Much like the youth section of the Labour Party, which includes members fourteen to twenty-four years of age, Young Democratic Socialists of America’s (YDSA) campus-centric program is oriented toward high school and college students, and, while democratic, mirrors the structure and campaign priorities of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). The endurance of the Woodcraft Folk highlights the unique value of cooperative, child-centered, family-friendly institutions for political and social development.

In a time of growth and institution-building, the American left must, please, think of the children. Young people are and should be just as invested in questions of peace, labor, and solidarity as anyone, and a movement like the Woodcraft Folk empowers them to confront these questions and grow into the leaders who will respond to them with the words of British socialist William Morris: “that we shall cry peace to all men and claimed kinship with every living thing: that we hate war and sloth and greed, and love fellowship, and that we shall go singing to the fashioning of a new world.”