Socialist Candidates Can Win Working-Class Voters of All Colors

Socialist candidates in recent years have tended to struggle with poor and working-class black voters. But new data from the New York City election shows that’s not inevitable: we can build a base that draws in the entire working class.

Supporters of Tiffany Cabán cheer her victory in the Queens District Attorney Democratic Primary election, 2019. (Scott Heins / Getty Images)

One of the most striking trends in New York politics over the past five years has been the transformation of Western Queens into one of the city’s socialist strongholds. Every year, campaign cartographers give us maps that show the borough’s western edge — from Astoria Heights to Hunters Point — awash in whichever color they chose to represent the most left-wing candidate on the ballot. Every year, four clusters of election districts are conspicuous in their defiance of the new local consensus. They remain islands of support for establishment politics amidst a rising tide of socialism, one pouring deeper inland each election cycle as if from the East River itself.

These districts are home to the only NYCHA developments in Western Queens: Astoria Houses, Ravenswood, Queensbridge, and Woodside Houses. They’re holdouts against the trends sweeping across their half of the borough because geography is only a rough proxy for how such changes actually move through society: via relationships between people in real community with one another. Public housing residents here, like in the rest of the city and cities across the country, are cut off in so many ways from the communities that surround them. Disproportionately poor and black, they approach politics with a much different history, and a different understanding of how best to navigate the challenges posed by the capitalist order. For years, the Left has failed to pose a compelling alternative.

Last week’s election results show that — in Astoria at least — we may be finally making some progress.

Cynthia Nixon won the 36th Assembly District, encompassing nearly all of Astoria, by more than fourteen points in the 2018 Democratic primary for governor. That margin would have been much closer if Astoria Houses weren’t carved out into the neighboring 37th Assembly District, where a narrow outcrop sneaks northward along Vernon Boulevard to join the development politically with nearby Ravenswood and Queensbridge.

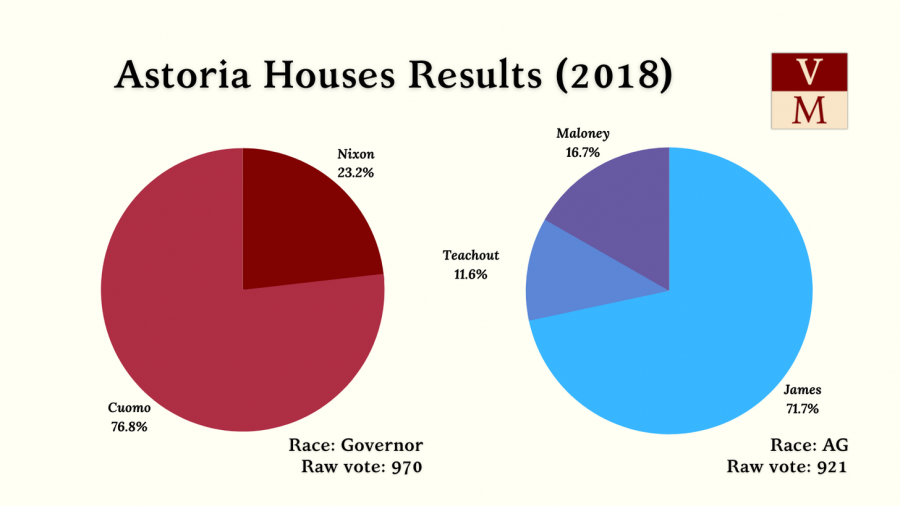

Nixon got less than a quarter of the vote in Astoria Houses — thirteen points worse than her statewide margin. Zephyr Teachout, the progressive nominee for Attorney General, faired even worse.

Remarkably, Nixon’s running mate for Lieutenant Governor, Jumaane Williams, lost the development to the incumbent Kathy Hochul. Though he came within thirty votes, Williams — a black man from Brooklyn with unimpeachable credibility on issues of racial justice and advocacy for black and brown New Yorkers — couldn’t prevail against a moderate white woman from upstate.

It’s as clear an illustration as you could ask for of the challenges confronting the Left in developing a base within poor and working-class communities of color. Of course there are the structural disadvantages, such as funding, name recognition, the ability to dispense patronage, and relationships with local power brokers. But there’s also the fact that these communities are the most exposed to the depredations of capitalism and the state violence that upholds it. As such, when it comes to politics, they place a high premium on proven relationships that have a history of yielding results: tangible, material improvements to their lives.

Sure, the Left says we can build the power to challenge the system that so stringently limits how good those improvements can be, but you have to admit at this point it’s still mostly theoretical — in the American context, anyway. People with the most to lose require a little more convincing, and they’re perfectly rational in doing so.

In 2019, Tiffany Cabán appeared on the ballot in Astoria Houses for the first time in her run for Queens District Attorney. Though she came within fifty votes of winning that entire election, she drew the bulk of her support from progressive whites, Hispanic voters, and some Asian communities all primarily in Western Queens. She struggled considerably with black voters living in the borough’s Southeast.

The results from Astoria Houses are notable for three reasons. First, they show that neither black voters nor NYCHA residents are a monolith; Cabán did much better here than in other NYCHA developments elsewhere in Queens. Second, they show that even granting that fact, there’s still work to be done to get to where we want to be: strong majority support from New York’s multiracial working class.

Finally, they show that this support can be built over time, if the Left doesn’t let its momentary losses go to waste.

Last week, Cabán won a majority of voters in Astoria Houses, doing better there than she did in the 22nd Council District overall. It was the first time in the post-Bernie left resurgence beginning in 2016 that a left-wing candidate carried the development in a Democratic primary.

Cabán even edged out Eric Adams in terms of vote share, and certainly drew support from a large number of residents who supported Adams for mayor.

The Cabán-Adams voter is proof of concept that the Left can build its base with poor and working-class communities of color over time, even if it doesn’t win them all at once. The takes are pouring in fast and furious from posters of every ideological persuasion about what the results of the mayoral election are telling us the People Really Want. I can’t speak for the entire demos, but what this person really wants is for allegedly serious observers of politics to stop reinforcing the fallacy that ideology plays anything other than a supporting role in election outcomes.

What people want is to be represented by someone they trust is looking out for them — someone they relate to, who they feel like they know. Familiarity and consistency are the bases on which trust can be built, and delivering results for working people is what builds that trust to last. Ideology matters, but it matters because that’s what tells us how to fight and what to fight for. It’s the fruits of that struggle that voters see and respond to more than anything else, and certainly more than a candidate’s tweets.

So the struggle continues — slow as always — but with a few more comrades than before.