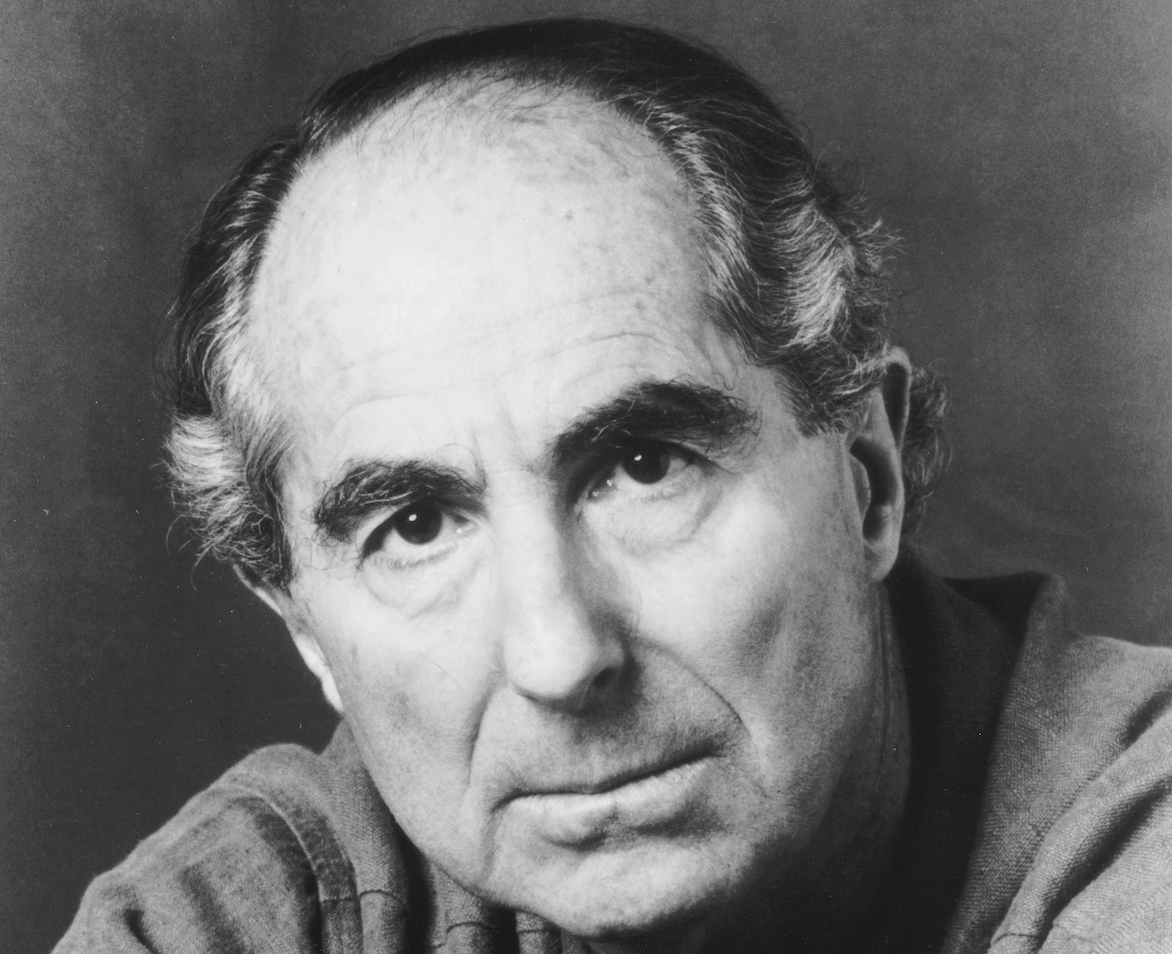

Philip Roth (1933–2018)

Philip Roth's work could only have been written by someone who came of age during the peak of postwar liberalism.

Nancy Crampton / Stanford University

Recently, I was practicing reading with my six-year-old when we got into a discussion of whether you can start a sentence with the word “and.” I was reminded of a line from Philip Roth, who died this week at eighty-five, from the 1998 novel I Married a Communist. The narrator is remembering his childhood love of Norman Corwin’s radio dramas, a staple of Popular Front culture. He recalls that they were his first sense of what storytelling should be, ending with the aside: “And taught me, contrary to what my teachers insisted, that I could begin a sentence with ‘and.’” My son took a while to get it, then exploded with joy. “Because that sentence starts with ‘and!’” It was delightful: his first Roth joke. Breaking a fake grammatical rule might seem pretty mild on the scale of Roth’s subversions, but it seemed appropriate. Throughout his five-decade career, Roth held to the insistence that the more a person or a culture insisted on a rule, the more nonsensical it likely was.

Roth’s early works attracted attention for their focus on the particularities of his world as a youth: the Popular Front, baseball, the war, and the fine distinctions among those Jewish immigrants of various levels of assimilation and middle-class aspirations. In the thirtieth anniversary edition of his first book, the short-story collection, Goodbye Columbus, he remembered:

In the beginning it amazed him [Roth] that any literate audience could seriously be interested in his story of tribal secrets, in what he knew, as a child of his neighborhood, about the rites and taboos of his clan — about their aversions, their aspirations, their fears of deviance and defection, their embarrassments and ideas of success.

It was against this backdrop that Roth’s early rebellions took off, earning ire from a range of quarters. Irving Howe famously criticized him for writing from a “thin personal culture” rather than the Jewish immigrant tradition Howe became famous for enshrining. More bizarrely, rabbis took to the pulpits to condemn him and hold forums to express their “concerns” over stories like “The Conversion of the Jews,” in which Ozzie, a young Sunday school boy, earnestly and reasonably wonders why, if God could create the world in six days, he couldn’t also be the father of Jesus. At a forum at Yeshiva University on “minority writers,” where Roth shared the stage with Ralph Ellison, the first question he was asked was, “Would you write the same stories you’ve written if you were living in Nazi Germany?” The implication was that Nazis were everywhere and no one should tell tales out of school. Roth responded in a range of ways, including imagining a romance with Anne Frank in The Ghost Writer. In his own way, Roth anticipated arguments made decades later by Peter Novick and Norman Finkelstein, about how the central role of the Holocaust in American life and culture stifled honest debate. Today, while liberal Jews scratch their heads about how their community could have produced a Sheldon Adelson and a Jared Kushner, Roth’s irreverence for the pieties of the Jewish establishment seem poignantly relevant. Many years after the dust up at Yeshiva, the hero of Sabbath’s Theater would imagine the obituary the establishment would write for him: “Mr. Sabbath did nothing for Israel.” It’s one of that prickly character’s best redeeming qualities.

Along with his fellow Newark native Allen Ginsberg, Roth is often credited with bringing a new level of sexual frankness to “serious” literature — and doing it in such a way that the idea of seriousness itself was thrown into question. “Businessmen are serious. Movie producers are serious. Everybody’s serious but me,” Ginsberg wrote in “America,” in the process of outlining just how depraved the so-called serious ones really were. For Roth, writing about sex was partly about considering how both our public and private stories were distorted by the need to appear more serious, more rational, and less cruel than we really were. But it was also about a rigid, repressive sexual order — and about how one might use the power of sex to avenge oneself against the powerful. The great feminist critic and essayist Vivian Gornick has written about how Goodbye Columbus displays a tenderness towards the central sexual relationship that would disappear by the time Portnoy’s Complaint came out in the late 1960s, making Roth a full-fledged celebrity:

In Portnoy’s Complaint, probably for the first time in Jewish-American literature, woman-hating is openly associated with a consuming anger at what it has meant to be pushed to the margin, generation after generation; humiliated time and again into second-class lives; deprived, in egalitarian America, of a place at the table in matters of social importance. For men like Bellow and Roth, the sense of pent-up outrage was so intense that it was inevitable not only that it vent itself on those closest to hand but that it confuse them with the powers that be.

In that, Roth actually shared more than a little with the feminists who would critique him and whom he would parody in turn. It is easy to forget that the suburban home was compared to a concentration camp not by Roth but by Betty Friedan, often seen as the staid face of liberal, mainstream feminism. Radicals like Kate Millett and Shulamith Firestone shared much of Roth’s sense that sex was a battlefield. Like many second-wave feminists, Roth wrote about how puritanism, the double standard, and fear of pregnancy distorted sexual relations. Two lesser-known books from the time when sex seemed more in flux than ever before, When She Was Good and My Life as a Man, draw on Roth’s tumultuous first marriage, portraying women driven mad by the drive to complete the domestic script. Ironically, these portraits, arguably the most misogynist in Roth’s cannon, perhaps inadvertently make a point that many feminist critics would also note around the same time: how the denial of sex pushed women to be arbiters of a false morality rather than fully realized (if conflicted) beings. It was a point he kept returning to: late in his career, in the dark, short novel Indignation, he posits the penalty for a single sexual transgression as death, as the protagonist is expelled from school and drafted into the Korean War. Later, in Sabbath’s Theater, he finally enters the post–sexual revolution world, creating a heroine with pathologies and neurosis to match those of her male counterpart, whose sexuality was not a reflection of his but a mark of her own tragedy and outsiderness.

Rather than assuming the male world as fixed, as many male writers have done, Roth’s work took masculinity as its topic and, intentionally or not, invited women to write back. Tributes emphasizing Roth’s status as the last of the literary lions with no “rightful successor” miss this. They celebrate his irreverence, but want someone new to write like him or with him, rather than against him. They ignore writers like Mary Gaitskill, coming of age in the post–sexual revolution world and grappling with how sexuality and power challenge our sense of ourselves as fixed and decent people. Or Anya Ulinich, whose recent graphic novel, Lena Finkle’s Magic Barrel (named for a story by Bernard Malamud, one of Roth’s models and mentors), contains a brilliant section in which the protagonist imagines her own romantic adventures being evaluated by Roth with a combination of bravura and self-deprecation Roth would certainly have appreciated.

Also ignored in most of the tributes is how, late in his career, Roth took on what may have been his most subversive and “anti-American” — in the best sense — topics of all: failure, aging, illness, and death. This happened not in the American trilogy, where nostalgia for the post–World War II era dulled his satirical edge, but in works like Patrimony, a nonfiction account of his father’s life, illness, and death, which ends with Roth cleaning up his father’s shit. Late works like Everyman and especially Sabbath’s Theater detail the costs of trying to live outside the traditional family in a culture without many viable alternatives, particularly when it comes to the care we need at the end of our lives. “Old age,” the narrator of Everyman reflects, “isn’t a battle: Old age is a massacre.” There are devastating portraits of how the cruises and art classes offered to the elderly fall far short of recompense for the loss of youth and health in a culture obsessed with avoiding frailty. This is where Roth departs most completely from Woody Allen, who presented a version of Roth in Deconstructing Harry more curdled and bitter than anything found in the work itself. When Roth’s older men follow their lust and disappointed ambitions, there is humiliation and pathos, not the increasingly ridiculous and horrifying fantasy fulfillment that became Allen’s shtick, if it hadn’t been all along.

The other big theme of Roth’s late work was the postwar history that shaped him. American Pastoral looks at the New Left through the eyes of a bewildered liberal father who can’t understand his radical daughter, I Married a Communist deals with how McCarthyism ruined the gentle hero of the narrator’s youth, and The Human Stain tells the story of an African-American professor who spent his career passing for white, set against the backdrop of the Lewinsky scandal. The triumvirate is often seen as Roth’s greatest accomplishment — possibly for the more obviously “serious” themes — and there is brilliant, powerful writing in all three works. But Roth’s own sense of absurdity, usually his strongest tool, here stands in the way. McCarthyism, the violence of the Weather Underground, the puritanism unleashed by the Clinton scandal — all of these are seen as a kind of inexplicable madness rather than endemic parts of our responses to American history and power: “What the hell happened to our smart Jewish kids?” the father of a young radical wonders in American Pastoral. “If, God forbid, their parents are no longer oppressed for a while, they run where they think they can find oppression. Can’t live without it. Once Jews ran away from oppression; now they run away from no-oppression. Once they ran from being poor; now they run away from being rich.” This is the character’s view and not Roth’s — and yet, throughout the book, there seems to be no room for imaginative sympathy for the radicals, no way to see them as they might see themselves, no possibility they might have genuine moral horror at their government’s murderous war.

For the young Roth, declaring that there weren’t Nazis behind every bush was a way of taking on the pieties of his community; but in this later work, the sense that the horror was always something over there shaded his perspective. This is particularly evident in The Plot Against America, a counterfactual history in which Charles Lindbergh is elected president and turns the United States fascist. As Keith Gessen has argued, the book flips the argument of his early works: what if the scolds had been right all along and the Nazis had been here in America? But its historical imagination falters, as Gessen notes:

“It is not here, and not now, that the Jew is being slaughtered,” James Baldwin once wrote, “and he is never despised, here, as the Negro is.” That’s never felt truer than in this strange book, where so many of the things Roth imagines happening to the Jews under Lindbergh have in fact happened in this country — to blacks. Roth’s Holocaust novel becomes something like a Holocaust anti-novel, where the crucial point appears to be that what’s happening on the page has never actually happened in life.

As in most current discussions about the possibility of fascism in America, which have sometimes evoked the novel, it misses the fact that, to paraphrase William Gibson, “fascism is already here, it’s just unevenly distributed.”

Still, there are places where the nostalgia and lyricism of these books preserve and record something important. Where I Married a Communist looks back lovingly at Popular Front culture, American Pastoral contains painfully lyrical tributes to the factories and labor that made Newark. And Roth had a great reverence for the relatively robust public institutions that marked those years, for the teachers that educated him, and, especially, for libraries. The Newark public library plays a key role in Goodbye Columbus, and unlike most famous writers, he donated his private library with annotated works not to a university collection but to the public library of his youth.

Roth’s death brought forth the predictable laments for the “end of an era” of great authors. Silly as these pronouncements are, Roth’s passing — and his work — is one mark of the fading of a different, specific order. Much as his work was filled with the cries of individuals bristling against the constraints of community and propriety, they could only have been written by someone who came of age in the heyday of postwar liberalism, who recognized many of its limits, hypocrisies, and, especially, its ultimate fragility.