The July Days

The Bolsheviks wanted to avoid the Paris Commune's fate. That’s why they didn’t take power in July 1917.

Political demonstration on June, 18, 1917, at Petrograd. The left banner reads “Peace to the Whole World — All Power to the People — All Land to the People” and the right banner reads: “Down with the minister-capitalists”; these were Bolshevik slogans.

In 1917, Russia had more than 165 million citizens, only 2.7 million of whom lived in Petrograd. The capital city held 390,000 factory workers — a third women — 215,000 to 300,000 garrisoned soldiers, and around 30,000 sailors and soldiers stationed at the Kronstadt naval base.

Following the February Revolution and Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication, the soviets, led by the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, ceded power to an unelected provisional government bent on continuing Russia’s involvement in World War I and delaying agrarian reform until after the Constituent Assembly election, the date of which was soon indefinitely postponed.

Those same soviets had also called for the creation of soldiers’ committees and instructed them to disobey any official orders that ran counter to the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies’ orders and decrees.

These contradictory decisions produced a shaky, dual power structure marked by regular government crises.

The first of these crises broke out in April 1917 over the war and ended after the main bourgeois political leaders — Pavel Milyukov from the Kadet (Constitutional Democratic) Party and Alexander Guchkov from the Octobrist Party — were ousted. Further, it revealed the government’s impotence in the Petrograd garrison: troops responded to the Petrograd Soviet’s Executive Committee rather than to then-commander General Lavr Kornilov.

The coalition government that emerged from this crisis included nine ministers from the bourgeois parties and six from the so-called socialist parties. Prince Georgy Lvov remained prime minister and minister of interior, but Minister of War and Navy Alexander Kerensky, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, soon became the government’s rising star. The cabinet also included Mensheviks Irakli Tsereteli as minister of posts and telegraphs and Matvey Skobelev as minister of labor. Socialist Revolutionaries Viktor Chernov and Pavel Pereverzev also joined the coalition as minister of agriculture and minister of justice, respectively.

The Bolshevik Party in Summer 1917

The Bolsheviks struggled for the first half of 1917. They initially opposed the International Women’s Day demonstration, which led to the February Revolution. The Bolshevik Party then experienced a sharp rightward shift in the middle of March, when Lev Kamenev, Joseph Stalin, and M. K. Muranov returned from Siberia and took over the party organ, Pravda. Under their control, the paper advocated critical support for the Provisional Government, rejected the slogan “Down with the War,” and called for an end to disorganizing activities at the front.

These positions contrasted sharply with the views Lenin expressed in his “Letters from Afar,” so it’s not surprising that Pravda published only the first of these, with numerous deletions. According to Alexander Shlyapnikov’s testimony:

The day of the appearance of the first number of the “reformed Pravda,” March 15, was a day of triumph for the “defencists.” The whole of the Tauride Palace, from the members of the Committee of the Duma to the Executive Committee, the very heart of revolutionary democracy, was brimful of one piece of news — the victory of the moderate and reasonable Bolsheviks over the extremists. In the Executive Committee itself, we were met with venomous smiles.

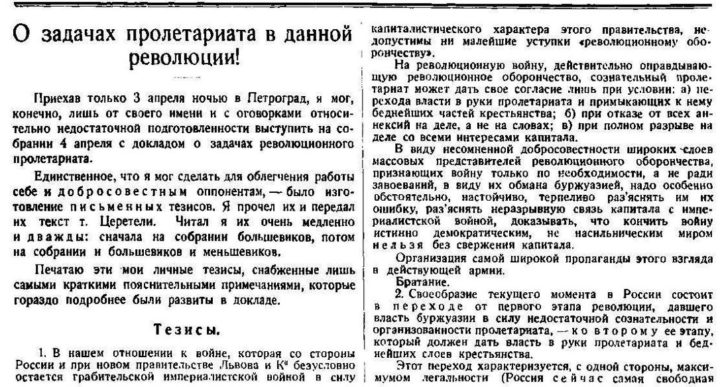

These views prevailed among Bolshevik leaders in Petrograd when, on April 3, Lenin arrived at the Finland Station. The following day, he presented his famous “April Theses” to the Bolshevik delegates to the All-Russia Conference of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. In contrast to Kamenev and Stalin, Lenin reaffirmed his total repudiation of “revolutionary defensism” and advocated fraternization at the front. He also adopted Leon Trotsky’s perspective, characterizing the “current moment” as a transition between the first “bourgeois-liberal” stage of the revolution and the second “socialist” stage, during which power would be transferred into the hands of the proletariat.

Lenin opposed Stalin and Kamenev’s “limited support” for the Provisional Government, calling instead for its complete rejection and dispelling the notion that the Bolsheviks and the less-radical Mensheviks might reunite. From then on, the Bolsheviks called for the transfer of all power to the Soviets, which would then arm the people, abolish the police, army, and state bureaucracy, confiscate all landlord estates, and transfer control of production and distribution to workers.

At the Seventh (April) All-Russian Conference of the Bolshevik Party, held in Petrograd from April 24 to 29, Lenin’s positions on the war and the Provisional Government won majority support.

The Bolshevik party remained small at the beginning of 1917, with only about two thousand members in Petrograd, constituting just 0.5 percent of the city’s industrial working class. By the opening of the April Conference, however, party membership had risen to sixteen thousand in the capital alone. By late June, it had doubled. Two thousand garrisoned soldiers had joined the Bolshevik Military Organization, and four thousand more had become associated with Club Pravda, a nonparty organization for military personnel operated by the Bolshevik Military Organization.

This massive growth in membership transformed the organization. Its ranks swelled with impetuous recruits who knew little about Marxism but were eager for revolutionary action.

Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks began incorporating existing organizations. On May 4, the day before the coalition government’s formation, Trotsky returned from exile. Now that he and Lenin had found common ground, Trotsky began connecting his organization, the Mezhraiontsy or Inter-District Organization of Petrograd, to Lenin’s party.

Despite this exponential growth, the Bolsheviks were still in the minority. They accounted for less than 10 percent of the delegates to the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies which opened on June 3. This national meeting included 1,090 delegates — 822 of whom could vote — which represented over three hundred workers’, soldiers’, and peasant soviets and fifty-three regional, provincial, and district soviets. The Bolsheviks had the third-largest representation with 105 delegates, behind the Socialist Revolutionaries (285 delegates) and the Mensheviks (248 delegates).

At this time, Petrograd had three distinct Bolshevik Party organizations: the nine-man Central Committee, the All-Russian Military Organization, and the Petersburg Committee. Each had its own responsibilities, subjecting them to different and sometimes conflicting pressures. The Central Committee, which had to consider the whole country’s situation, often found itself restraining the more radical groups.

Setting the Stage

The Bolshevik Military Organization planned an armed demonstration for June 10 to express mass opposition to the Provisional Government’s preparations for a military offensive, Kerensky’s attempts to reinstitute discipline in the barracks, and the increasing threat of transfer to the front. It canceled the action at the last minute, bowing to the Soviet Congress’s opposition.

Some elements in the Bolshevik Party, particularly in the Petersburg Committee and the Military Organization, saw the aborted demonstration as a potential uprising. Indeed, Lenin himself had to appear at an emergency meeting to defend the Central Committee’s decision to cancel the planned mobilization. He explained that the Central Committee had to follow the Soviet Congress’s formal order and that the counterrevolution intended to use the demonstration for its own purposes. Lenin added:

Even in simple warfare it happens that scheduled offensives must be canceled for strategic reasons and this is all the more likely to occur in class warfare. . . . It is necessary to determine the situation and be bold in decisions.

The Congress of Soviets voted to stage its own march a week later, on June 18, and ordered all garrisoned military units to participate, unarmed. The Bolsheviks turned this into a massive demonstration against the government, with over four hundred thousand protesters.

In his eyewitness account of the Russian Revolution, Nikolai Sukhanov recalls:

All worker and soldier Petersburg took part in it. But what was the political character of the demonstration? “Bolsheviks again,” I remarked, looking at the slogans, “and there behind them is another Bolshevik column.” . . . “All Power to the Soviets!” “Down with the Ten Capitalist Ministers!” “Peace for the hovels, war for the palaces!” In this sturdy and weighty way worker-peasant Petersburg, the vanguard of the Russian and the world revolution, expressed its will.

The Bolsheviks had planned the original demonstration with the Petrograd Federation of Anarchist-Communists, one of the two major anarchist groups operating at that time. The Anarchist Provisional Revolutionary Committee decided to outdo its ally and broke F. P. Khaustov, editor of the Bolshevik Military Organization’s frontline paper, out of Vyborg prison.

In response, the government raided the anarchists’ headquarters, killing one of their leaders. Combined with Kerensky’s July Offensive and new orders for weapons and men, Asnin’s murder intensified military unrest, particularly in the First Machine Gun Regiment. These soldiers began planning an immediate uprising — with encouragement from the Anarchist-Communists — as early as July 1.

At the All-Russian Conference of Bolshevik Military Organizations, the delegates were warned not to play into the government’s hands by staging a disorganized and premature uprising. Lenin’s speech on June 20 sounded a prescient warning:

We must be especially attentive and careful, so as not to be drawn into a provocation. . . . One wrong move on our part can wreck everything. . . . If we were now able to seize power, it is naive to think that having taken it we would be able to hold it.

We have said more than once that the only possible form of revolutionary government was a Soviet of Workers’, Soldiers’, and Peasants’ Deputies.

What is the exact weight of our fraction in the Soviet? Even in the Soviets of both capitals, not to speak now of the others, we are an insignificant minority. And what does this fact show? It cannot be brushed aside. It shows that the majority of the masses are wavering but still believe the SR’s and Mensheviks.

Lenin returned to this idea in a Pravda editorial:

The army marched to death because it believed it was making sacrifices for freedom, the revolution, and early peace.

But the army did so because it is only a part of the people, who at this stage of the revolution are following the Socialist-Revolutionary and the Menshevik parties. This general and basic fact, the trust of the majority in the petty-bourgeois policy of the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries, which is dependent on the capitalists, determines our Party’s stand and conduct.

But, in Trotsky’s words, the workers and soldiers:

[R]emembered that in February their leaders had been ready to beat a retreat just on the eve of the victory; that in March the eight-hour day had been won by action from below; that in April Miliukov had been thrown out by regiments who went into the street on their own initiative. A recollection of these facts augmented the tense and impatient mood of the masses.

Unit-level leaders of the Petrograd Military Organization largely supported immediate direct action against the Provisional Government, and many rank-and-file Bolshevik Party members already considered an early uprising inevitable and even desirable.

Just when the offensive was about to collapse, however, the government spiraled into another crisis: four Kadet ministers left the coalition, protesting Kerensky’s compromise with Ukraine’s Central Rada. This abrupt defection left the government, now composed of six socialist and only five capitalist ministers, disorganized and vulnerable. As the July Days began, the Bolsheviks won a majority in the workers’ section of the Petrograd Soviet, testifying to their growing influence among the masses.

The Armed Demonstration

The series of events known as the July Days began on July 3, when the First Machine Gun Regiment launched a rebellion with the support of a number of other military units. The outbreak of the uprising coincided with the Bolsheviks’ Second Petrograd City Conference, which opened on July 1.

Only when it became clear that that several regiments, supported by masses of workers, had already taken to the streets and that rank-and-file Bolsheviks were participating did the Central Committee join the movement and recommend that the demonstrations continue the next day under Bolshevik auspices. Although the Central Committee understood that the protesters would carry weapons, the recommendation said nothing about an armed uprising or the seizure of government institutions. Instead, the official resolution reiterated the Bolshevik call for “the transfer of power to the Soviet of Workers’, Soldiers’, and Peasants’ Deputies.”

Thus the Bolshevik Military Organization assumed leadership of a street movement that had originally developed outside its control. The unexpected eruption threw the party into disarray. Those who obeyed the Central Committee and argued in favor of postponing the revolution found themselves in conflict with others, particularly members of the Military Organization and the Petersburg Committee, who favored immediate action.

Of course, a revolutionary party experiences exponential growth during a revolution: we saw already that the Bolshevik party in Petrograd grew by 1,600 percent in less than five months. This subjects the party to unprecedented pressure, which manifests with varying degrees of intensity in different party organs and threatens to tear the organization apart.

No organizational arrangement can prevent this; a whole set of circumstances — among them the trust the party leadership has won — impact how revolutionary events unfold. That is why building a party cannot be undertaken in the heat of the moment, as the German Revolution would demonstrate.

On July 3, the armed demonstrators unsuccessfully attempted to arrest Kerensky before moving on to the Tauride Palace, the seat of the Soviet Central Executive Committee. They intended to force this group to seize power from the Provisional Government.

The multitude — estimated at sixty to seventy thousand people — overwhelmed the palace’s defenses and presented its demand. The executive committee refused. Trotsky captured the irony of the moment when he observed that, while hundreds of thousands of protesters were demanding that soviet leaders take power, the leadership itself was looking for armed forces to use against the demonstrators.

In the aftermath of the February Revolution, the workers and soldiers had given the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries power, but these parties tried to hand it over to the imperialist bourgeoisie, preferring a war against the people to a bloodless transfer of power into their own hands. When the July demonstrators realized that the Soviet leadership would not dispense with its capitalist allies — most of whom had left the government on their own anyway — the situation reached a stalemate.

“Take Power, You Son of a Bitch, When It’s Given to You!”

The following day, Lenin, who was away in Finland, went straight to the Bolshevik headquarters, the Kshesinskaia mansion. Soon sailors from the Kronstadt naval base arrived there as well. Lenin’s last public speech until after the October Revolution was not what the sailors had expected: he emphasized the need for a peaceful demonstration and expressed his certainty that the slogan “All Power to the Soviets” would win out. He concluded by appealing to the sailors for self-restraint, determination, and vigilance.

The July Days cast the Bolshevik Central Committee, and particularly Lenin, in a most unusual light: they prevented a premature uprising in the capital which, had it succeeded, could have isolated the Bolsheviks and crushed the revolution, as happened to the Paris Commune in 1871 and to the Spartacist Uprising in Berlin in 1919.

An estimated sixty-thousand-strong procession headed for the Tauride Palace, only to meet sniper fire at the corner of the Nevsky and Liteiny Street and again at the corner of the Liteiny and Panteleymonov Street. The most casualties, however, came from clashes with two Cossack squadrons, who even employed artillery against the demonstrators. After these pitched street battles, the Kronstadt sailors, led by Fyodor Raskolnikov, reached the Tauride Palace, where they joined the First Machine Gun Regiment.

Then, one of the most dramatic and tragicomic events of the day took place: Victor Chenov, the Socialist Revolutionaries’ so-called theoretician, was sent out to calm the protesters. The crowd seized him, and a fist-shaking worker told him: “Take power, you son of a bitch, when it’s given to you!”

They declared Chernov under arrest and took him to a nearby car. Trotsky’s timely intervention saved the minister. Sukhanov described the bizarre scene:

The mob was in turmoil as far as the eye could reach. . . . All Kronstadt knew Trotsky and, one would have thought, trusted him. But he began to speak and the crowd did not subside. If a shot had been fired nearby at that moment by way of provocation, a tremendous slaughter might have occurred and all of us, including perhaps Trotsky, might have been torn to shreds. Trotsky, excited and not finding words in this savage atmosphere, could barely make the nearest rows listen to him. . . . When he tried to pass on to Chernov himself, the ranks around the car began raging. “You’ve come to declare your will and show the Soviet that the working class no longer wants to see the bourgeoisie in power [declared Trotsky]. But why hurt your own cause by petty acts of violence against casual individuals? . . . Every one of you has demonstrated his devotion to the revolution. Every one of you is ready to lay down his life for it. I know that. Give me your hand, Comrade! Your hand, brother!” Trotsky stretched his hand down to a sailor who was protesting with especial violence. But the latter firmly refused to respond . . . It seemed to me that the sailor, who must have heard Trotsky in Kronstadt more than once, now had a real feeling that he was a traitor: he remembered his previous speeches and was confused. . . . Not knowing what to do, the Kronstadters released Chernov.

Chernov returned to the Tauride Palace and wrote eight editorials condemning the Bolsheviks. The Socialist Revolutionary journal Delo nadora finally published four of them.

The Provisional Government as a whole, however, took revenge in a much more perfidious way: the next day, it began a slanderous campaign that described Lenin — who had reached Russia by traveling through Germany in a sealed train — as an agent of the German General Staff.

Reaction’s Temporary Triumph

On July 5, the Soviet Central Executive Committee and the Petrograd Military District launched a military operation to reassert control of the capital. Troops loyal to the government occupied the Kshesinskaia mansion and wrecked Pravda’s publishing plant. Lenin barely escaped.

It is idle to speculate whether, had he been caught, he would have met the same fate as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in the aftermath of the Spartacist Uprising, but we can find a clue in a caricature published in the right-wing newspaper Petrogradskaia gazeta two days later:

Loyal troops also occupied the Peter and Paul Fortress, which the First Machine Gun Regiment surrendered at the behest of the Bolshevik Military Organization. The Central Committee of the Party instructed its followers to terminate the street demonstrations, calling on the workers to return to work and on soldiers to return to their barracks.

Meanwhile, the government ordered the arrest of leading Bolsheviks including Lenin, Kamenev, and Grigory Zinoviev as well as Trotsky and Anatoly Lunacharsky, the heads of the Inter-District Organization. Although some of these political prisoners, including Trotsky, left jail during the Kornilov coup to organize the workers’ resistance, others would stay in prison until the October Revolution.

Thus ended the July Days, which were, in Lenin’s words, “something considerably more than a demonstration and less than a revolution.”

Some of the Bolshevik Party’s main leaders had to go underground, and its newspapers closed, but the setback was short-lived. The Eleventh Army’s failed offensive on the southwestern front against a massive Austro-German counterattack, paired with the deteriorating economic situation, renewed the Bolshevik slogans’ validity.

Indeed, the Bolshevik newspapers soon reappeared with slightly altered names, and the party committees found new footing very quickly. Disarming the rebellious military units, as the government ordered, was easier said than done. Soon the defeat of the Kornilov coup in August 1917 reversed the situation, finally creating the conditions for the Bolsheviks’ successful bid for power.