What’s Good for Boeing Workers Is Good for the Public

On the West Coast, 33,000 Boeing workers are in the midst of the US’s largest strike. It’s not just wages and benefits at stake — it’s the question of whether we will continue to have skilled, secure workers making goods as delicate and complex as airplanes.

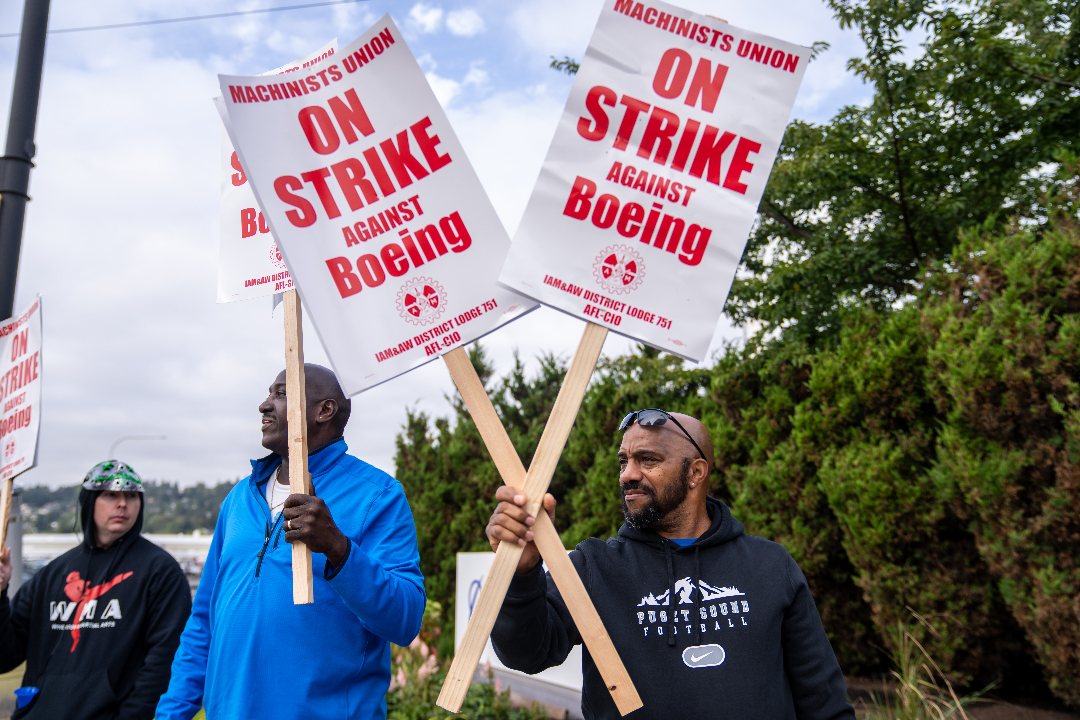

Boeing Machinists union members picket outside a Boeing factory on September 13, 2024, in Renton, Washington. (Stephen Brashear / Getty Images)

On Friday, some 33,000 Boeing workers went on strike after voting down a tentative agreement (TA) reached on September 8 between their negotiating committee and the airplane manufacturing giant. The strike by the workers — members of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM), most of whom work at the company’s gigantic Everett, Washington, plant, the largest manufacturing building in the world — is now the largest active work stoppage in the United States. It’s the first strike at Boeing since 2008.

Boeing CEO Robert “Kelly” Ortberg, installed earlier this year after the company suffered yet another publicity nightmare when the cabin panel of a 737 MAX 9 came off midflight in January — not to mention the highly suspicious deaths of two whistleblowers at the company — practically begged the workers not to strike, stating that the walkout puts Boeing’s “recovery in jeopardy.”

“We encourage them to negotiate in good faith — toward an agreement that gives employees the benefits they deserve and makes the company stronger,” White House spokesperson Robyn Patterson said on Friday. Negotiations resumed on Tuesday, with a federal mediator present at the bargaining table.

Boeing machinists’ average pay has risen 15 percent over the past decade to $75,000. For workers faced with the soaring cost of housing in the Seattle area, that’s a far cry from the family-sustaining wage enjoyed by prior generations at the plant.

“Boeing is saying they are in a tough spot recovering yet their executive salaries haven’t changed,” a Boeing mechanic told the Guardian. “It is much deeper than pay and benefits. It is Boeing’s culture. We are a family here in my shop.”

Indeed, despite mounting debt, Boeing does not lack for money when it comes to executive pay: Ortberg stands to make $22 million next year, while his predecessor Dave Calhoun got a 45 percent raise in 2023; the company has spent some $68 billion on stock buybacks and dividends since 2010.

“This is about addressing the past, and this is about fighting for our future,” IAM District 751 president Jon Holden said in announcing the vote to strike, which saw 96 percent of ballots in favor of a strike. The TA was voted down by 94 percent.

The striking workers at Boeing want higher wages and stronger benefits — the TA they voted down included a 25 percent wage increase over the course of the four-year contract, compared to the 40 percent sought by the union, as well as the reinstatement of robust pensions given up in 2014. But worker power and product safety are intimately related at Boeing. The twin crashes of Boeing’s 737 MAX 8 airliners in 2018 and 2019, which killed 346 people, are very recent history, and the January malfunction suggests continued reason for concern. (Former CEO Dennis Muilenburg, who was ousted following the crashes, left with a golden parachute of $62 million.)

The company’s nonunion workforce has ballooned since the company began shifting production in 2009 to North Charleston, South Carolina, where it now produces the 787 Dreamliner jet. The move south was a way of undercutting the unionized workforce on the West Coast, who had just gone on strike — a blatant enough act of union busting that the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint against the company, alleging that the move had been taken to avoid labor unrest and was “inherently destructive” of workers’ rights. South Carolina has the lowest unionization rate of any state.

A company shifting production to a nonunion plant is worthy of criticism in itself; it’s undercutting workers’ wages, working conditions, and rights to collectively bargain. But at Boeing, it also poses enormous risks.

The manufacturer’s high wages and strong benefits in Washington ensured skilled workers remained at their posts for decades, accumulating expertise and experience that is critical in the production of airplanes. When higher-ups tried to cut corners to boost the bottom line, these workers could at least try to intervene to save lives. Workers with little experience and even less job security are far less equipped to do the same.

Take William Hobek, a quality manager at the South Carolina plant. Hobek filed suit in a federal court claiming that he’d been fired after reporting defects up the chain of command. As Peter Robison writes in Flying Blind: The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing, a supervisor told Hobek, “Bill, you know we can’t find all defects.” Writes Robison, “Hobek called over an inspector, who quickly found forty problems. Other employees describe defective manufacturing, debris left on planes — wrenches, metal silvers, even a ladder — and pressure not to come clean about it.” It’s one of several cases of workers alleging that they were pressured not to report faulty production.

That is what Boeing wants airplane production to look like. Perhaps more than any other major employer, they have proven themselves incapable of being trusted by the public and workers alike. The unionized workers in Washington may be striking for higher wages and benefits, but their victory will be a win for the public, both in the United States and around the world.

Would you rather fly on a plane built by people who take pride in their work and have long tenure at their post, or by harried workers, exhausted from overtime or a second job, green, with the most experienced among them having quit as soon as they could? We need workers who know when Boeing’s next cost-cutting measure will endanger the rest of us, and the only ones who have the proven experience to do so are currently on the picket line.