The Anti-Capitalist Origins of the Monopoly Man

The new PBS documentary Ruthless: Monopoly’s Secret History tells the story of how a board game intended to warn Americans about inequality ended up teaching them how to be good little capitalists.

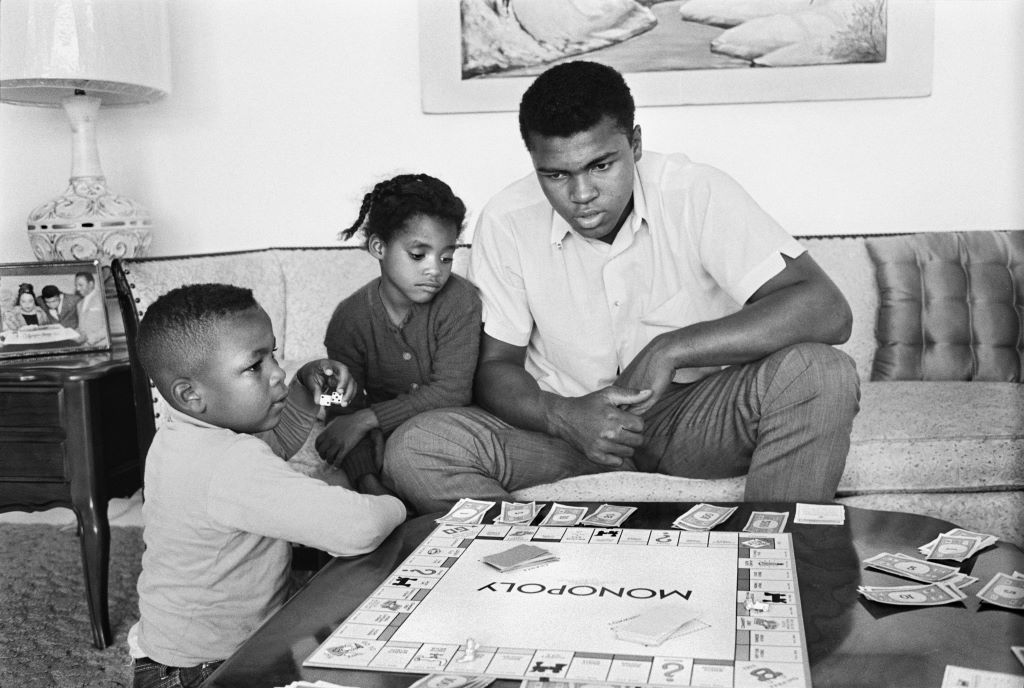

Muhammad Ali and children playing Monopoly at home. (Steve Schapiro / Corbis via Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Ed Rampell

“The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas.” Theoreticians have applied Marx and Engels’s concept to analyses of literature, theater, cinema, academia, punditry, and more. But who would have thought that the same framework could also be brought to bear on the most popular board game in history?

In Ruthless: Monopoly’s Secret History, writer/director Stephen Ives not only explores what the game Monopoly tells us about our economic system, but takes us behind the scenes to reveal its surprising origins as a piece of political agitprop, chronicling the courageous, real-world trustbuster behind the game who challenged and exposed the United States’ corporate behemoth in a David versus Goliath courtroom struggle of epic proportions.

Ives’ other American Experience documentaries for PBS include 2003’s Seabiscuit and 2019’s Roads to Memphis, about the shadowy life of James Earl Ray and his fateful collision with Martin Luther King. In the late 1990s Ives also made the mammoth series The West, which was executive produced by Ken Burns, with whom Ives shared an Emmy for 1990’s The Civil War.

Jacobin took a roll of the dice and was lucky enough to monopolize Stephen Ives’ time for an interview about Ruthless.

So why do a documentary on a board game?

The first board game published in the United States was The Mansion of Happiness in 1843. It was published by William and S. B. Ives Company [W. & S. B. Ives], my great-great-grandfather and his brother. They eventually sold it to Parker Brothers. The Mansion of Happiness was the classic nineteenth-century board game, which was incredibly boring: all it was about was inculcating moral lessons to the kids who played it.

Could the same be said about Monopoly?

Where else do we bow down and worship at the altar of unbridled capitalism, the way we do with Monopoly? It’s this rite of passage that we do generation after generation. It’s the way we introduce our children to money, property, and real estate. On some levels it’s this deeply American celebration of our deeply capitalist system. The game has now been customized by players. There was always a bucket of money in the middle and if you landed on “Free Parking,” you got all that money, because whenever people had to pay “Luxury Tax,” “Chance,” “Community Chest,” you put it in the center of the board. That’s actually not in the rules and pumps more liquidity back into the system — it’s one of the reasons the game goes on forever. If you play it by the rules, it’s a game that is usually over in two hours.

As a game, it’s a mythic idea about American life and culture. Everyone starts with the same amount of money and has access to the bank, no matter who you are. The winner is always the smartest one at the table. And luck only plays a part in making a player the winner, because they know how to play the game the right way. That’s a very self-serving narrative about what American capitalism is all about. What’s kind of ironic is that the game was based on a myth, as well.

What’s the Parker Brothers’ official origin story for Monopoly?

Charles Darrow stole the game, basically, in 1935. His story, his “rags to riches” invention that made him a millionaire, was such a powerful narrative for people in the Depression; they wanted to hear stories like that. Parker Brothers [which mass produced the game] found out it was a lie, but they stuck with it, because it was such a great narrative and way to tell a happy story. Americans wanted to hear it — and in a way they still do.

Who was Elizabeth Magie and what was The Landlord’s Game?

She was one of the more interesting women I’ve come across in my thirty years of looking at American history. She was the daughter of a successful newspaper publisher who was a friend of the young Abraham Lincoln. She was exposed to lots of interesting ideas growing up. She was a performance artist, an inventor, and a feminist. She was really pushing boundaries in her day. I really admire her; she was way ahead of her time.

She was a disciple of this intellectual Henry George, a famous writer and lecturer who believed inequality in American life came from the fact that we didn’t tax land properly. Land was communal, and if landlords were sitting on land, they were getting income they hadn’t really earned, and the secret to creating a more level playing field in American life was to tax land. He called it “the single tax theory.”

Lizzie became a huge fan of that idea and hoped to promote Henry George’s ideas, and decided to do it through the mechanics and rules of a board game, which no one had tried before. After lots of years of tinkering with the idea she came out with The Landlord’s Game in 1904. It’s a square board, with four railroads, “Chance” cards, a jail in the corner and free parking — they don’t call it “Go,” but you get money every time you go around the board and cross a square called “Mother Earth.” It’s all of the most fundamental aspects of Monopoly, right there. And she just thought about and worked at it.

Unfortunately for Lizzie, her goal was for it to be a critique of capitalism. But it turned out to be a celebration of it.

Was she a socialist?

I don’t think she might have called herself that, but she certainly had socialist leanings. She was very much a leftist. She believed the Gilded Age created tremendous amounts of inequality in the United States — which, obviously, it did. And she felt like there was a way to give the workingman and woman a fairer shake, and thought Henry George’s theories were the way to get it.

Was she a feminist?

Oh, yeah. At one point, she took out an ad where she advertised herself as “a young American woman slave” to the highest bidder. To her dismay, people started sending in offers. The Pulitzer newspaper, the World, started doing these big pieces on her. She was basically trying to point out that the workingwomen of the United States were captive to their husbands and a society that didn’t give them freedom. As a stunt, it was a work of genius.

What role did Quakers play in the history of Monopoly?

One of the things that’s cool about the game is that it’s a very early example of a viral phenomenon. It takes off in very small ways and starts spreading on college campuses. I don’t think Lizzie Magie was aware of this. Everybody started customizing the game and putting their own streets and neighborhood onto their boards, which they made by hand.

It ended up landing with a group of Quakers in Philadelphia, and they took it down to their vacation places in Atlantic City and started adding the names of the properties that have become iconic: “Boardwalk,” “Baltic,” “Mediterranean,” and “Oriental”; “Kentucky Avenue” was the black nightlife district in Atlantic City. There’s a whole picture of the United States’ favorite destination playground of the 1920s reflected in the streets that the Quakers chose to put on their board.

Unwittingly, the Quakers were reflecting redlining and segregation at the same time. They were putting “Baltic” and “Mediterranean” down as the lowest prices on the board — those were mostly the black neighborhoods in Atlantic City. The green properties were more middle-class Jewish properties. “Boardwalk” and “Park Place” were obviously where the richest people were hanging out. It is a snapshot of class and race. If you look underneath the board itself, underneath that iconic design, you find something a little more complicated.

Tell us about Ralph Anspach.

I met Ralph in 2005. That’s when I shot the interview with him that’s in the film. I came across his self-published book called The Great Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle and I thought, that’s interesting. I sought him out. The film didn’t work out then, but eighteen years later American Experience said, “We love this idea! Let’s do it.”

Ralph was almost the cliché of the rumpled, distractable academic. He had the corduroy blazer and the hair all over the place. But he was a very sharp guy, a Jewish émigré from Germany who fled the Nazis with his family. They’d been given help when they first got to America by the Quakers. He was pissed off by monopolies in the 1970s, by the gas prices going up, by OPEC. And he came up with this game Anti-Monopoly. That was his idea of a better way to organize society. He was also unwittingly doing the same thing Lizzie Magie had tried to do: to use a board game to communicate a strong social message.

He got sued by General Mills, the cereal conglomerate that had swallowed up Parker Brothers. If it happened to you or me, and you got a scary cease-and-desist letter from a multinational corporation, you’d probably say, “I’m sorry! I’m sorry!” and walk away. But Ralph said: “No way.” He sued them first to get jurisdiction in California and embarked on a ten-year legal crusade to prove that his game was completely separate from their game, and that there was no way that their trademarks should be confused: One is Monopoly; the other is the exact opposite, Anti-Monopoly.

In the end his case went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. It was a long struggle for Ralph. The Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco ruled in his favor. Most of blue-chip America filed amicus briefs in support of General Mills, and they took it to the Supreme Court. And the Supreme Court denied to hear the case. The Ninth Circuit ruling held.

It’s a good thing for Anspach that he didn’t appear before today’s Supreme Court.

You’re telling me! Before ultimately prevailing, Ralph lost twice, and the great irony of this is that he took out three mortgages on his home to try and pay for the lawsuit. He mortgaged his property to fight Monopoly! The other incredible irony of this is that as soon as Parker Brothers realized that Charles Darrow was lying and was a fraud and didn’t invent the game, they had a huge problem on their hands, because their best-selling hero and his game were fraudulent. So, they went out and tried to buy up all of the other folk games and other games that have been publishing with Monopoly as their inspiration. So, they were trying to monopolize the game of Monopoly! I mean, you can’t make this stuff up!

All of the secret history that had been hidden ever since Lizzie Magie had invented the game in 1904 and Darrow claimed to invent it in 1935 was finally unearthed and made public for the first time. It was Ralph’s research and efforts to get to the bottom of the story that unearthed Monopoly’s secret history. He even found Magie’s 1904 patent in the Patent Office. That must have been this incredible epiphany for him, because suddenly he was looking at the absolute blueprint of the board game Monopoly, from over thirty years before Darrow claimed to have invented it.

There are other left-wing board games. On the cover of the game Class Struggle is a picture of Nelson Rockefeller arm wrestling Karl Marx.

What I learned in this story is that board games are really a unique and powerful place. When you enter into a game — some of the people in the film talk about this, especially [game designer] Eric Zimmerman — you’re playing a role in a way you don’t in any other aspect of life. There’s a way in which habits or actions or ways you exist inside a game space have a very powerful way of teaching things. That’s one of the things interesting about Monopoly: it’s inculcating into children and young adults, this system, this belief system, this totemic idea that this is the way the economic system is meant to work.

It’s an unbridled, winner-take-all, relentless crushing-of-the-opponents kind of worldview. That’s why Monopoly is a fascinating lens through which to look at American culture and life. It’s also ultimately a cautionary tale, because all of the things you’d like to brush over are embedded in this story: greed, corporate machinations, and the idea that someone like Lizzie Magie is the kind of person who often gets cast aside in an economic system like ours.

Circa 1967. (Graphic House / Archive Photos / Getty Images)

What’s so fascinating to me about Ralph and his heroic struggle, Lizzie and her incredibly passionate idealism, and Parker Brothers and General Mills’ corporate domination is that it really does reveal a very clear-eyed look at how the real world works and how American capitalism functions. I just think it’s always important for us to keep that in the forefront of our mind when we think about everything good and challenging about what this country represents.