The Cold War Is Over. It’s Time to Appreciate That Eugene Debs Was a Marxist.

For decades, many of Eugene Debs’s admirers have claimed that the socialist leader was a good, patriotic American unsullied by a foreign doctrine like Marxism. But the Cold War is over, and there’s no need to be defensive: Debs was a Marxist who rightly opposed American nationalism.

Labor activist Eugene V. Debs speaks at the Hippodrome in New York City in 1910.

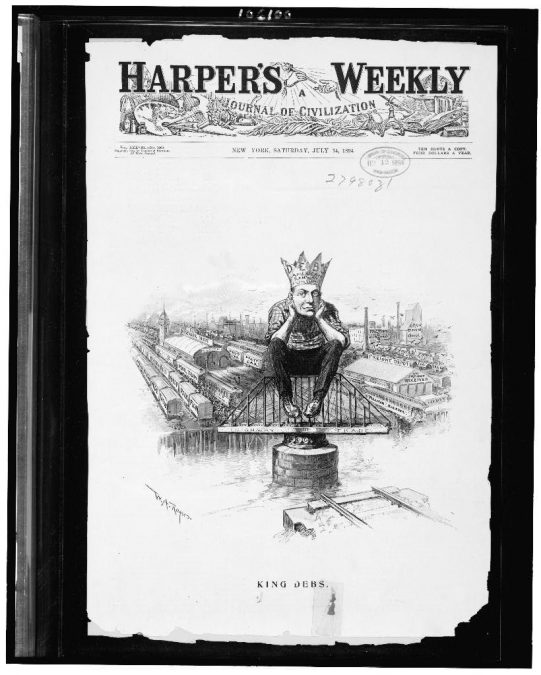

Throughout his life, Eugene Debs was smeared as an enemy of the American nation. During the 1894 Pullman strike, Harper’s Weekly attacked Debs’s leadership of the uprising as equivalent to Southern secession, claiming that in “suppressing such a blackmailing conspiracy as the boycott of Pullman cars by the American Railway Union, the nation is fighting for its own existence.” Thirty years later, when Debs was imprisoned for speaking against World War I, President Woodrow Wilson denied requests to pardon him, refusing to show mercy to “a traitor to his country.”

Debs’s sympathizers have often defended him against allegations of treason by highlighting his authentic Americanism. Rather than a traitor, they claim, Debs was a true patriot who stood up for nationally shared ideals like freedom and democracy while imbuing them with socialist values. Historian Nick Salvatore, for instance, argues in his landmark 1982 biography that Debs’s life “was a profound refutation of the belief that critical dissent is somehow un-American or unpatriotic.” Inspired by Debs’s example, socialists today might occupy the left flank of a progressive patriotism, pushing the United States to make good on its democratic promise in a way that liberals and centrists cannot do on their own.

Despite some intuitive appeal, this nationalist strategy is a dead end for the Left. At a basic level, democratic nationalism presents the nation as bound by a shared identity and shared interests, uniting different classes behind a common project domestically and internationally. In the United States, this project has only ever been a variant of capitalist empire that, even when grafted to the cause of democracy, has been deeply inhospitable to the strategic thinking and moral fiber that can sustain the Left.

In his own time, Debs rejected that kind of nationalist project, making his politics more than the radical edge of common sense “Americanism.” When Debs called out the absurdity of the wartime view that patriotism means dying overseas for capitalist profits while treason consists in defending workers everywhere, he showed us the proper response to nationalist ideology: not to try to hijack it for progressive ends, but to liberate us from its obfuscations.

Today, when the Left is often conscripted into a project to defend democracy rather than re-create it, Debs can still offer us guidance. Recalling what Marxism taught Debs can show us how the dominant themes of American democratic discourse — especially its conceptions of property, freedom, and self-rule — do not provide a foothold for a democratic left. Instead, they obscure our path toward a just society at home and abroad.

American Democracy vs. Marxism

In 1948, at the outset of the Cold War, historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr edited an anthology of Debs’s speeches and writings. No socialist himself, Schlesinger wanted to establish Debs’s place within an American democratic tradition weaponized against Marxism.

In his introduction to the volume, Schlesinger argued that the source of Debs’s unique popularity as a radical leader was not socialism, but democratic nationalism. He emphasized that when Debs agitated for socialism, he did so “in a spirit so authentically American — so recognizably in the American democratic tradition — that under his leadership the Socialist movement in this country reached its height.” American workers were not inspired by Debs’s condemnation of wage slavery, but were swayed by his homespun oratory, which expressed a “profoundly intuitive understanding of the American people” nurtured by his small-town Indiana upbringing. “Men and women loved Debs,” Schlesinger asserted, “even when they hated his doctrines.”

According to Schlesinger, the popularity of an “Americanized” socialist like Debs shows that progressives have nothing to lose by rejecting class struggle, inhabiting the cultural mainstream, and working within the two-party system. Through the ordinary electoral process, a liberal party could fulfill working-class demands by curbing the political power of business, defending democratic rights and freedoms, and guiding capitalist growth according to an inclusive sense of the public good.

Most of all, Schlesinger sought to show that Marxism was as foreign to Debs as it was to America. Among the US left, he singled out Debs for praise because, in his view, Debs was always closer to liberal democratic Americanism than Marxist totalitarianism. Debs’s inveterate patriotism “made him avoid the syndicalist terrorism of the I.W.W. or the conspiratorial disloyalties of the American Communist Party.” Rather than threaten the nation, Debs stood before a jury of his peers to defend freedom of speech when liberal governments had sacrificed their true principles in a moment of wartime fervor. And as an inveterate democrat, Debs could never accept the revolutionary Marxist program of proletarian class rule, nor could he sacrifice immediate associational freedoms for the sake of historical progress, both of which threatened a totalitarian takeover of democratic institutions.

Ultimately, Schlesinger saw Debs as a useful figure to make a broader argument about the place of the Left in progressive politics. Like Debs (or so Schlesinger imagined), leftists should accept the basic justness of American democratic institutions, inhabiting a position of critical dissent that holds liberals to account without ever exercising real independent power.

Why Debs Was a Marxist

Schlesinger’s story distorts the historical record. Debs was a democrat, but he was also a Marxist and an internationalist. He believed that working-class democracy was only possible if workers controlled the capital infrastructure they set into motion, operating it according to social principles entirely different from those of the profit-seeking capitalist market.

Yet despite these elementary facts of Debs’s politics, reigning discussions of his life remain deeply Schlesingarian. Salvatore’s biography downplays Marxism’s formative influence on Debs, arguing that “the roots of his own social thought remained deeply enmeshed in a different [American] tradition” — namely, Protestant Christianity and the egalitarian settler individualism of Jefferson and Lincoln. In a 2019 essay in the New Yorker that draws on Salvatore’s account, historian Jill Lepore portrays Debs as an honorable figure because his politics “had less to do with Karl Marx and Communism than with Walt Whitman and Protestantism.”

So why did Debs become a Marxist? Anyone familiar with Debs lore knows that he probably encountered Marxist theory for the first while imprisoned for his leadership of the Pullman strike. Milwaukee socialist Victor Berger delivered Debs The Class Struggle, by Karl Kautsky, and Marx’s three volumes of Capital.

But theory alone would not have brought Debs to socialism if it did not clarify his experience in the labor movement. When Debs claimed that the Pullman strike was his “first practical lesson in Socialism, though wholly unaware it was called by that name,” he did not refer to his prison reading, but the strike itself: “in the gleam of every bayonet and the flash of every rifle the class struggle was revealed.” At the same time, Marxism provided the intellectual framework that Debs used to make sense of this experience, liberating him from strategic misconceptions and giving new meaning to the struggles that defined his life.

Debs was introduced to the labor movement through the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF), a trade group that was as much a workers’ civic organization as a trade union. While it helped workers exercise some control over their employment (for instance, by regulating hiring and firing), it often collaborated with management to prevent strikes and spread a culture of workplace discipline. When BLF workers joined the country’s first national strike wave in 1877, the organization quickly condemned their lawlessness.

Over the course of a decade in the BLF, Debs became impatient with the organization’s division of workers into isolated trades and its antipathy to strikes. Debs came to believe that workers’ demands could only be met if all railway workers united in a single industry-wide union that could bring recalcitrant employers to the bargaining table through disciplined industrial action. In 1893, Debs helped found the American Railway Union (ARU), with the hope that an industrial union of all the nation’s railroad workers could ensure workplace safety, good wages, and real opportunities for participation in decision-making on the job.

At this point, Debs’s hopes for industrial unionism represented the radical edge of an emerging national consensus about the relationship between capital and labor. According to this consensus, “capital” referred to the tools used by labor. If this was true, capital and labor needed each other: capital would be idle without labor, and labor powerless without capital. The key to the “labor problem” was therefore uniting both parties around common interests and protecting the rights of each — solidifying protections for private property while allowing workers a measure of associational freedom. For his part, Debs insisted that he was “not engaged in any quarrel between capital and labor. There can be no such quarrel unless it is caused by deliberate piracy on one side and unreasonable demands on the other.”

According to Debs’s early theory, the reason why capital so often dominated labor (and why labor was unable to exert control over capital) was that workers were too disorganized on the job and in politics. En route to supporting the People’s Party, Debs came to believe that labor should not only organize industrial unions, but also organize politically in a working-class party to defend against elite capture of the nation’s democratic institutions, restoring power to the sovereign people.

The Pullman strike began to undermine Debs’s belief that capital and labor had common interests and that capital’s political power could be overcome by working-class organization within the capitalist state. After workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company south of Chicago went on strike and sought out the ARU in a desperate plea for assistance, Debs and the union organized a sympathy boycott of Pullman cars around the country, refusing to hitch the luxury sleeping cars to trains or receive trains under Pullman control. Commerce radiating out of the Chicago metropolitan area ground to a halt, triggering a national crisis.

The specter of an industrial union controlling what could be shipped on the rails while claiming to be the true representative of the country’s railway workers was too much for the American capitalist class and the American state. Rather than treat workers as parties to a contract trying to enforce their right to jointly set its terms, the press blasted them as seditious rioters and called for Debs’s immediate arrest, denouncing him as an aspiring dictator trying to subject the railways to his personal will.

A coalition of railway owners conspired with the attorney general to issue a federal injunction against the strikers (an unprecedented tactic that the Supreme Court only ruled legal after the fact), the Democratic administration called in the national guard against the strikers, and Debs was sent to jail.

The episode showed Debs that when workers exercise control over both capital and their own labor at the industry-wide level, it is regarded as an overwhelming crisis, not the assertion of democratic bargaining rights. Without realizing it, the ARU was not striking for equal rights within a democratic state but at the core of capitalist power: its command of labor backed by the right to private property.

Property and Freedom

In his early years, Debs had accepted the sanctity of private property while insisting that labor had an equal right to shape how property was used. When Debs became a Marxist, he abandoned what is perhaps the cardinal myth of American nationalism: that private property and freedom are intimately connected. According to the dominant political narrative — one deeply shaped by the United States’ settler colonial origins — a free person is someone who has private access to the economic basis for personal independence. In early America, the surest route to this kind of republican freedom was private ownership of land or small capital. With open access to private property, every settler would have an equal chance to acquire property and bargain with others, creating a nexus of voluntary agreements among free and equal partners. In these circumstances, the right to private property was a sacrosanct protection against domination, since it protects the material basis of an individual’s free independence.

After his encounter with Marxism, Debs came to view the right to private property not as the basis of liberty, but a title to despotism. In his speeches and writing, Debs began to integrate Marx’s understanding that “capital” is not merely a useful object — machinery and tools — but a form of social power over labor. As Marx put it in a widely circulated address to the International Workingmen’s Association (which Debs quoted in a 1904 pamphlet), “Capital does not consist in accumulated labor serving living labor as a means for new production. It consists in living labor serving accumulated labor as a means of maintaining and multiplying the exchange value of the latter.” In other words, the capital infrastructure that workers use to produce commodities is not merely a valuable set of tools that they use to satisfy society’s needs. Under capitalism, the labor process that makes capital productive is designed so that the investment it represents returns a profit.

In Marx’s view, capital and labor do need each other, as Debs’s early theory held: capital can only become productive through collective labor, and workers with nothing but their labor to sell rely on wages to meet their needs. The young Debs also intuited the right goal: labor should control capital, not the other way around. But if Marx’s analysis is right, then labor is not dominated by capital because of disorganization, but because of capitalism’s inherent features: private ownership of capital, production for the market, and property-less wage labor structure basic economic relationships to the disadvantage of the working majority. If labor really wanted to control capital in the general interests of society, workers needed to challenge the institution of private property outright.

While strong unions can increase labor’s share of the economic pie and institutionalize a form of industrial democracy, Marxism helped Debs see that unions alone cannot remove labor’s dependence on capitalists for access to work, a dependence that, in the context of market competition, capitalists inevitably use to ratchet down wages and working conditions. To transcend this domination — rather than limit ourselves to “perfecting wage servitude,” as he once put it — workers must dispense with the illusion that private property rights in a capitalist society protect universal freedom, as the early settler vision held. In capitalism, private property primarily protects domination, not liberty.

When Debs rejected the traditional American ideal of propertied individual independence, he came to think of freedom as rooted in the shared enjoyment of socially produced wealth. In Debs’s mature view, comprehensive security should be provided to all as a matter of right, with everyone’s living standard raised equally in proportion to technological progress. Economic liberty would not be realized in the pursuit of individual advantage but through collective self-government: participating in democratically planned production and distribution according to need.

Dilemmas of Popular Sovereignty

After his encounter with Marxism, Debs was adamant that capitalist society could never be made just. No justice was possible in a society where workers were robbed of the fruit of their labor in exchange for access to work, and where they were kept artificially poor amid rising abundance. Seized by the conviction that anything short of capitalism’s overthrow was compromise with injustice, Debs became a strident revolutionary.

Debs often discussed revolution as the realization of democracy, making its promise of popular sovereignty real. For some interpreters, this emphasis on popular sovereignty places Debs within a distinctly “American” consensus. The Constitution’s preamble, after all, begins with “We, the People,” and the Declaration of Independence establishes its claims on the basis that the people are the ultimate authority in politics.

But popular sovereignty is an easy ideal to abuse, making this supposed consensus too contradictory to be coherent. The Supreme Court’s majority opinion in the In re Debs case, which justified sending Debs to prison without a trial by jury during the Pullman strike, argued that suppressing the strike had defended the people from the disruption of a lawless minority. Calling in the National Guard to break the strike should serve as “a lesson which cannot be learned too soon or too thoroughly that under this government of and by the people the means of redress of all wrongs are through the courts and the ballot box.” Woodrow Wilson justified entering World War I to “make the world safe for democracy,” presenting American institutions as a bulwark of democratic freedom in a world of authoritarian threats. “Suppose every man in America had taken the same position Debs did,” Wilson declared. “We would have lost the war and America would have been destroyed.”

In Debs’s estimation, these claims about democracy emptied the ideal of its true substance: popular power through collective action. When workers in Pullman’s company town bucked their rulers, that was self-government in action, not the assertion by unelected judges that commerce must continue, whatever its social costs. And if democracy means that the people rule themselves collectively as equals in all dimensions — economically and politically, at home and abroad — then democracy’s foes are much more comprehensive than Woodrow Wilson’s concern about political authoritarianism. Democracy’s enemies include all the ways that our capacity for free cooperation in self-government is hampered. Were workers in democratic America no less the slaves of their capitalist masters than workers in authoritarian Germany?

A Democratic Revolution

The strategic question of how a movement for socialism can make good on the promise of popular self-rule deeply divided Marxists in Debs’s day. Debs himself often tried to appease different factions in the socialist movement to preserve internal unity, so retrospectively, it can be easy for various camps to claim him as their own. Cold War liberals like Schlesinger can point to Debs’s refusal to join the Communist Party as evidence of his democratic Americanness. Social democrats can appeal to the Socialist Party’s municipal successes under his national leadership. Revolutionaries can highlight his praise of the Spartacist uprising in Germany and the Bolshevik revolution.

Any honest account of Debsian democracy should emphasize that Debs believed in a democratic revolution that would fundamentally remake American political and social institutions. If capital and the state formed part of an integrated social system, it was an illusion to think that the forms of democracy permitted by American institutions could be radically weaponized against capitalist power. Instead, a democratic power that might overcome capitalism had to spring from organizations substantially outside them.

That’s why Debs celebrated the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World as the “Continental Congress of the working class” and why, in 1912, the Socialist Party insisted their platform could only be realized alongside a constitutional convention. Rather than simply reference American historical anecdotes, Debs and other socialists announced a future rupture in historical time, where the basic terms of political legitimacy would be refounded. The basic logic of production and distribution would have to be organized along egalitarian lines, pushed forward by large-scale industrial unions working alongside the Socialist Party.

In the “democratic America” of his time, when the people were sovereign in name only, Debs saw institutions of class struggle as the primary site where workers could start to see that a more rational, self-determining society was possible and develop the capacities to create one. Through their own independent organizations, workers could begin to build a state within a state that could contend for power with the ruling class during capitalism’s inevitable crises.

Debs Today

The term “socialism” is more popular in American political discourse today than in decades. While this popularity is shallower than it is deep, we have a chance to dispense with Cold War myths and recall Debs’s politics fully and clearly, renewing the core of his political vision without the nationalist packaging.

From a Marxist perspective, the call for internationalism is not simply an ethical exhortation — that we should care about others around the world, just like we care for those close to us. Instead, it’s rooted in awareness of the real social interdependence that unites workers everywhere. This global interdependence, which has only intensified in the past century, is overladen with social misery even as it produces the possibility of a higher form of life, one that moves beyond myths of race and nation to grasp the collective power of humanity in making our world and controlling our common fate.

Today, that collective sovereignty often appears inconceivable in a world riven by crisis and fear. Debs was well-acquainted with both. Rather than acquiesce or seek shelter behind established power, his politics turned that fear on the ruling class. For the crises of their order might produce true democrats, like Debs, who would rob them of the might they mask as right.